New Documents in Snow Leopard's TextEdit

In the Snow Leopard version of TextEdit, you can now create a new document by Control-clicking TextEdit's Dock icon (when it's running), and choosing New Document from the pop-up menu. This isn't a major feature, of course, since you can also just press Command-N while in TextEdit, but consider Control-clicking other applications' Dock icons to see what functions they might make available.

Submitted by

Jerry Nilson

Recent TidBITS Talk Discussions

- Alternatives to MobileMe for syncing calendars between iPad/Mac (1 message)

- Free anti-virus for the Mac (20 messages)

- iTunes 10 syncing iPod Touch 4.1 (2 messages)

- Thoughts about Ping (16 messages)

Related Articles

- T-Mobile's Google Phone Promising but Unpolished (20 Oct 08)

- T-Mobile Introduces Branded Google Phone (23 Sep 08)

- Symbian Smartphone Platform Goes Free, Partly Open Source (24 Jun 08)

- Gauging Openness with iPhone as Measure (21 Jan 08)

- Apple Releases Mac OS X 10.4.11 with Safari 3 (14 Nov 07)

Published in TidBITS 904.

Subscribe to our weekly email edition.

- Stay Up to Date on Leopard Compatibility

- BBEdit 8.7.1 Adds Features, Fixes Bugs, Saves Data

- Freeverse Sponsoring TidBITS

- Word 2004 Crashing Bug Squashed

- New Apple Ads: Real, Fake, and Funny

- VMware Releases Fusion 1.1 Update, VMware Importer

- AT&T Offers New International iPhone Data Plans

- Design Tools Monthly Hits 15 Years in Print

- DealBITS Winners: SmileOnMyMac's TextExpander 2

- Spotlight Strikes Back: In Leopard, It Works Great

- Take Control News: All Leopard Titles Available in Print

- Hot Topics in TidBITS Talk/12-Nov-07

Google's View of Our Cell Phone Future Is an Android, Not a GPhone

I never expected Google to get into the consumer cell phone business, just like I never expected Google to build a national Wi-Fi network, nor, even if they win a spectrum auction in January 2008, do I expect Google to build a national cellular network. Google doesn't do hardware - they build ways in which to use hardware to reach more people to feed those people more ads. (Two minor exceptions, before you cavil: their Mountain View Wi-Fi network, serving their headquarters' town, and Google search appliances - server hardware for businesses.)

Last week's announcement of a consortium of cell carriers, chipmakers, and phone handset makers collaborating on a new cell phone platform confirms my worldview. Phones using this new platform will start shipping in the second half of 2008.

Control What Runs on the Phone -- The Open Handset Alliance is a response to the cell operating systems and associated software that dominate ordinary handsets and smartphones worldwide. While many platforms and carriers allow customization of phones by carriers, as well as post-purchase installation of software or utilities by customers - the iPhone so far being a rare exception - the underlying platforms are generally locked down. There are also licensing fees.

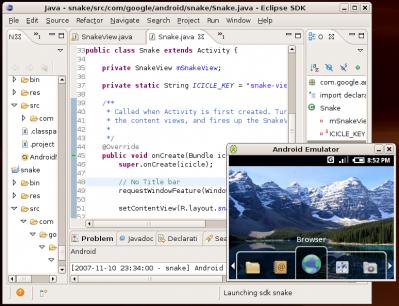

Google and its 33 partners will launch a platform named Android; a preview for developers is now available. Android uses Linux as a base, Java as the glue, and open-source components throughout (Android was the name of a firm Google acquired that was working on such a platform). The platform will be free to handset makers and end users for development and distribution, which explains the composition of the partnership. The Symbian platform has dominance worldwide, and the company that develops it is owned just a fraction under 50 percent by Nokia, the biggest handset maker worldwide. Microsoft's Windows Mobile, the Palm OS, and RIM's BlackBerry dominate in the United States. Linux-based cellular platforms are picking up steam worldwide, however, and this will accelerate that trend.

The marketplace for cell handsets is confusing, because we do things differently here in the United States than in much of the world. Most phones receive subsidization through multi-year service plan commitments, locked through encryption to a single carrier, and cannot be freely interchanged across networks. In Europe and in many other countries, consumers buy phones at full cost and then sign up for service at a much higher rate than here, but even more unusually phones are nearly universally unlocked - in some countries that's a legal requirement - and can be moved freely among carriers which all use an identical standard, reducing lock-in and requiring more creative competition for features and service offerings.

In the United States, we also have two incompatible network standards in use - GSM and CDMA - and thus you cannot switch easily from Verizon or Sprint Nextel (CDMA) to T-Mobile or AT&T (GSM). CDMA is used extensively in South Korea, and by carriers in Japan and China, too, while GSM is used by most of the rest of the world. While you can unlock a CDMA or GSM phone after a contract expires and activate that phone with a given American network, or purchase a GSM phone from abroad that's unlocked, these are relatively rare in practice. (Even more rare are specialized GSM/CDMA dual-protocol phones, which are typically expensive and designed for frequent international travelers.)

What this means is that cell carriers in the United States control access to their networks by allowing only a certain range of phones and other devices to connect. Microsoft may be a giant company, but it is still beholden to Verizon, AT&T, and the other carriers to get phones into people's hands; Apple, likewise, discovered this in having to commit to a single carrier and seemingly acquiesce to limits sought by AT&T in order to get the iPhone released. In Europe, Nokia has a slightly different position, because although it can't dictate features and phones to carriers, it can market directly to consumers, which enables it to offer a wide variety of phones.

In both marketplaces, the carriers rule. Innovative features from chipmakers may be ignored by the carriers, while handset makers other than Nokia are usually directed into making products that the carriers want. Even if Nokia inserts a feature it wants, carriers can keep that feature from being enabled on their networks; Nokia has plenty of phones that stream video, but that feature typically works only over Wi-Fi. Companies that are more involved with software than hardware find themselves stymied in getting their Web services or applications installed because of carrier objections.

Partners and Interests -- Who's involved in the Open Handset Alliance and why? Alliance members Broadcom, Intel, Marvell, Qualcomm, and TI are all chipmakers who are beholden to handset manufacturers to push their products into phones. By having a platform that they can build their own reference designs around, they have much more flexibility to find manufacturing partners outside the mainstream, or to deliver more interesting products to existing handset makers.

While Qualcomm controls a lot of fundamental cell technology through patents, notably on the CDMA standard, it doesn't control platforms. It's a rare move for Qualcomm to be part of an alliance promoting greater variety and less control, frankly.

What's also interesting about the alliance is that it includes major handset makers LG, Motorola, and Samsung, which are largely locked out of the current smartphone market. It's not that they don't have offerings, but they don't own any segment of the market. This is an attempt for them to leverage a new platform that no one controls, and that they can extend.

Carriers are also part of the alliance, with the two U.S. carriers who need a clue (T-Mobile and Sprint Nextel) along with some giants in Asia (China Mobile, KDDI, and NTT DoCoMo), and Telefónica, which has 212 million customers across Africa, Europe, and Latin America.

Other alliance members include eBay, which owns Skype, and which could potentially leverage this platform to produce a true Skype phone that could combine support for cell networks, Wi-Fi, and other wireless technologies; and Sirf, which is the biggest maker of GPS receiver chips in the world, and which would like to have more of them put into phones with more capabilities enabled.

Let's look next at how this fits together in different parts of the world.

What Do Carriers Gain? Of all the partners, you might wonder why carriers would find this alliance interesting. Self-preservation, among other reasons. Carriers want to be able to keep more of the revenue, and to be able to release more interesting phones more quickly to encourage upgrades. They want to tailor their offerings to particular markets and niches. All of these desires conflict with the slower pace, monolithic offerings, and centralized control of existing platforms.

In the United States, although Sprint Nextel is the third-largest carrier, the company is in a weak position. The company is losing subscribers in an awkward transition of former Nextel customers to new systems, and it mishandled an expensive and still-ongoing transition in a swap of frequencies with public-safety agencies. (It's a very long story.) Sprint Nextel's chief resigned a few weeks ago, and the company just scrapped its current plans to launch a mobile WiMax network alongside competitor and co-operator (in both senses of the word) Clearwire. (The deal may be off for now, but both firms say they're committed to mobile WiMax, and when a new CEO is hired at Sprint, a new deal could be put together. In fact, some reports indicated Sprint might purchase Clearwire or spin off its mobile WiMax division to merge with Clearwire.)

Mobile WiMax offers the potential for ubiquitous broadband wireless at rates matching today's wired broadband, and with higher speeds and fewer restrictions than current cell data networks. The WiMax commitment represents a huge risk for Sprint, and one that would cost billions to execute. Sprint Nextel needs a platform for its new WiMax network, which uses new spectrum, and had already inked a deal that would enable Google to offer services over this new network.

T-Mobile, the distant fourth-place U.S. carrier, has been pursuing different strategies for years, as they lacked sufficient spectrum to compete in the 3G market. In 2006, T-Mobile purchased licenses over which they can deploy 3G, but it still won't be enough to compete head-to-head with other carriers.

So T-Mobile has been investing heavily in a Wi-Fi network since acquiring the assets of an early firm that went into bankruptcy in 2002. The company now has one of the largest Wi-Fi networks in the world with over 8,500 U.S. locations, and thousands more worldwide. T-Mobile was the first to launch converged Wi-Fi/cell calling in the United States, too, using handsets that can seamlessly move calls in progress from a Wi-Fi network to a cell network and back again. Clearly T-Mobile needs to think different, too.

In China, there's always been a desire to have technology that isn't dependent on companies from other countries. It's why China has developed its own third-generation (3G) cellular, but also why their 3G deployment is so vastly delayed - no one else is working on it, so they lose the distributed creativity and economies of scale. It's not at all strange that a carrier in China would want a platform they didn't have to export currency to use, and one that could be entirely within their power to mold to local needs. (And, potentially, to local government control. I don't mean to introduce politics; it's simply a fact that Chinese telecommunications is designed for monitoring and interception. And I can't be smug about that anymore in the United States, can I?)

In other parts of Asia, I have less of an explanation, as I understand competition there less well. There's been a much longer-running trend in Japan for phones to have more advanced features, for network operators to allow more independent activity, and for consumers to pay for specific software features. Japanese carriers have used proprietary phones that provide lock-in, but limit their ability to continue to provide new features in a timely and cost-effective manner. That may all tie in together, too.

iPhone Versus GPhone -- Android will have much in common with the iPhone at the base level, but likely less so in terms of user interface and cell carrier experience.

Internally, the iPhone runs the Unix-based OS X; Android will use Linux. The iPhone uses swaths of open-source and free software from GNU and other foundations, associations, and independent programmers. Android will, too.

But pop up one more layer, and you find that while Android will give developers access to all those innards, ostensibly providing even kernel software code, the iPhone will never give up those secrets.

Handsets that use Android will have to adhere to a set of principles and be tested operationally against those ideas, and by passing tests should be allowed to operate on the network of a carrier that's part of the alliance. The iPhone is designed to work on a limited number of networks worldwide.

The iPhone software development kit (SDK) will allow some kinds of programs to be developed, but programs may require approval or certification from Apple and/or AT&T and other partner carriers before those programs can be distributed. The Android SDK will apparently allow any form of development and installation.

There's a lot of risk for carriers with Android; they must design their networks to isolate bad actors rapidly in order to avoid spreading viruses or having phones that suddenly act up and take the network down. That's a real fear, and one that Steve Jobs cited in Apple's interest in delaying an SDK for the iPhone until security issues were well-characterized and covered.

The Internet still works despite armies of zombie computers and vast quantities of spam because it's resilient. Cell networks aren't quite as tough and will need to become more hardened before Android phones can be let loose.

Google's Spectrum Bid -- To circle back around to Google, I mentioned early on that I didn't expect that even if they won a spectrum auction next year they'd run a cell network. This is where it all comes around.

By January 2008, the FCC will auction the last bit of prime frequencies that will be freed up on completion of the transition of television stations from the UHF band. This is the end of analog television broadcasting, set for 17-Feb-09. The so-called Upper 700 MHz auction has a number of licenses, but the one to watch is the "C Block" auction for 24 MHz of prime territory.

The 700 MHz band penetrates walls easily and a single base station can transmit over four times the area using the same power as a base station in the 2.5 GHz range, the spectrum that Sprint Nextel and Clearwire will use for mobile WiMax.

Google and other firms - some of which are in this alliance - lobbied the FCC to require open access rules that would mean three things:

- Any winning bidder of the frequency would have to sell access to the network on a non-discriminatory wholesale basis to any reseller

- Any device could gain access to the network

- Any device could access any service or run any application

None of the provisions could be construed to allow unlimited bandwidth at fixed prices or uses that would disrupt the network.

The FCC turned down the open-resale provision, but adopted most of the others, and has fought back carriers who opposed the rules. (The FCC has a backdoor, though. They required a minimum bid of over $4 billion for the C Block and $10 billion for the entire auction. If those minimums aren't met, the auctions will be conducted again without the open access requirements.)

Google indicated its willingness to bid on the spectrum, guaranteeing the minimum bid necessary, if all the rules were adopted. But they stated at the same time that even if they won, they'd be more likely to work with a partner that would build and run the network.

It was clear all along that Google wanted a national broadband wireless network that would be unimpeded by gatekeepers. Recall that Google feeds enormous amounts of data to customers of telephone companies and cable firms via DSL, cable, and fiber, and that those telephone and cable companies are interested in establishing a tiered network in which Google and others would have to pay to push their content through at the highest possible rates on each network.

Is it any wonder Google is promoting an open phone platform and some measure of openness in the last great wireless broadband spectrum auction?

Some folks we respect, including John Gruber, wondered or stated that Android was vaporware, which I found odd. Vaporware implies that you're announcing a product well in advance of shipping with nothing really in hand beyond a demo and with the intention of sabotaging competitors who are forced to explain to customers why they don't have The Amazing Feature that's in the vaporware - even though the vaporware isn't available. The iPhone would have been vaporware if Apple hadn't set specific expectations on availability and then lived up to those expectations. (Leopard had a few vaporware features that may return in later updates, especially in regard to Time Machine's support of networked drives.)

Given that the Android SDK shipped as promised in a form that anyone with developer chops can download and work with, that removes some of the vaporware taint. Whether a product can and will ship with Android software is, of course, another matter that only the future can prove to us.

Fake Steve Jobs, however, might have put it best, as he often does: "Companies don't form alliances and consortia when they're winning."

Tying It All Together -- Google is promoting something that's in its best interest, of course, but as a firm that generally attempts to make money by disseminating information as widely as possible, it's in our best interests, too. Google doesn't like gatekeepers or walled gardens.

In the end, it's conceivable that we could wind up with hundreds of companies making handsets that work across wireless networks of all sorts worldwide, providing us access to the latest software and technology at a fraction of what we pay now. That's one vision of the future, it's Google's vision, and Google seems to have the momentum to make a real go at it.

[Note: Article updated 13-Nov-07 with additional and corrected details about European handset purchasing, China's cell standards, and Japanese carrier motivations.]

SYNC YOUR PHONE with The Missing Sync: Sync your calendar,

SYNC YOUR PHONE with The Missing Sync: Sync your calendar,address book, music, photos and much more between your phone

and Mac. Supports ANDROID, BLACKBERRY, PALM PRE and many

other phones. <http://www.markspace.com/bits>