Facts at a Glance

Facts at a Glance

Full country name: Republic of Ireland, & Northern Ireland (part of the UK)

Area: 84,421 sq km/52,341 sq mi (70,282 sq km/43,575 sq mi in the Republic; 14,139 sq km/8,766 sq mi in the North)

Population: 5.2 million (3.6 million in the Republic; 1.6 million in the North)

Capital city: Dublin (population 1.5 million)

People: Irish

Language: English, Irish (around 80,000 native speakers)

Religion: 95% Roman Catholic, 3.4% Protestant in the Republic; 60% Protestant, 40% Roman Catholic in the North

Government: Democracy

Head of state: Mary McAleese (Republic), Queen Elizabeth II (Northern Ireland)

Prime Minister: Bertie Ahern (Republic), Tony Blair (Northern Ireland)

Small-beaked and wing-clipped, Ireland is an island in the Atlantic Ocean which appears about to alight on the coast of Britain 80km (50mi) to the west across the Irish Sea. It stretches 500km (310mi) north to south and 300km (186mi) east to west, and contains only two fully fledged cities of any size, so it's never far to isolated sweeps of mountain or bogland.

Much of Ireland's elevated ground is close to the coast, and almost the entire Atlantic seaboard, from Cork to Donegal, is a bulwark of cliffs, hills and mountains, with few safe anchorages. Most of the centre of the island is composed of flat farmland or raised bogs. This area is drained by the 260km (161mi) long Shannon, which enters the sea west of Limerick.

Landscape, myth & history: Ossian's Grave, County Antrim (24K)

Landscape, myth & history: Ossian's Grave, County Antrim (24K)

The Irish landscape and predominant flora that you see today are almost wholly the result of human influence. Before the famine, the pressure on the land was enormous and even the most inaccessible of places were farmed. On the hillsides, above today's fields, you can still occasionally see the faint regular lines of pre-famine potato ridges called lazy beds.

As a result of the pressure on the land, only 1% of the native oak forests which once covered Ireland remain, much of it now replaced by dull columns of plantation pine. Foxes and badgers are the most common native land mammals, but you might also spot hares, hedgehogs, squirrels, shrews, bats and red deer. Otters, stoats and pine martens are also found in remote areas. Many migrating birds roost in Ireland, and there are still a couple of native species lurking about: corncrakes can be found in the flooded grasslands of the Shannon Callows and parts of Donegal. Choughs, unusual crows with bright red feet and beaks, can be seen in the dunes along the western coastline.

Despite its northern latitude, Ireland's climate is moderated by the Gulf Stream, bringing the dregs of Caribbean balminess, as well as turtles and triggerfish. The temperature only drops below freezing intermittently during the winter and snow is scarce. Summers aren't stinking hot, rarely hitting 30° C (86° F), but they're comfortable and it stays light until around 11 pm. Whatever the time of year, be prepared for rain because Ireland is wet. The heaviest rain usually falls where the scenery is best, such as around Kerry, which can be drizzle-bound on as many as 270 days of the year. If you do find the rain getting you down you might find some comfort in the Irish saying: 'It doesn't rain in the pub'!

The Celts, Iron Age warriors from eastern Europe, reached Ireland around 300 BC. They controlled the country for 1000 years and left a legacy of language and culture that survives today, especially in Galway, Cork, Kerry and Waterford. The Romans never reached Ireland, and when the rest of Europe sank into the decline of the Dark Ages after the fall of the empire, the country became an outpost of European civilisation, particularly after the arrival of Christianity, between the 3rd and 5th centuries.

During the 8th century Viking raiders began to plunder Ireland's monasteries. The Vikings settled in Ireland in the 9th century, and formed alliances with native families and chieftains. They founded Dublin, which in the 10th century was a small Viking kingdom. The English arrived with the Normans in 1169, taking Wexford and Dublin with ease. The English king, Henry II, was recognised by the pope as Lord of Ireland and he took Waterford in 1171, declaring it a royal city. Anglo-Norman lords also set up power bases in Ireland, outside the control of England.

English power was consolidated under Henry VIII and Elizabeth I. The last thorn in the English side was Ulster, final outpost of the Irish chiefs, in particular Hugh O'Neill, earl of Tyrone. In 1607 O'Neill's ignominious departure, along with 90 other chiefs, left Ulster leaderless and primed for the English policy of colonisation known as 'plantation' - an organised and ambitious expropriation of land and introduction of settlers which sowed the seeds for the division of Ulster still in existence today.

The newcomers did not intermarry or mingle with the impoverished and very angry population of native Irish and Old English Catholics, who rebelled in a bloody conflict in 1641. The native Irish and Old English Catholics supported the royalists in the English Civil War and, after the execution of Charles I, Oliver Cromwell - the victorious Protestant parliamentarian - arrived in Ireland to teach his opponents a lesson. He left a trail of death and destruction which has never been forgotten.

In 1695 harsh penal laws were enforced, known as the 'popery code': Catholics were forbidden from buying land, bringing their children up as Catholics, and from entering the forces or the law. All Irish culture, music and education was banned. The religion and culture were kept alive by secret open-air masses and illegal outdoor schools, known as 'hedge schools', but by 1778, Catholics owned barely 5% of the land. Alarmed by the level of unrest at the end of the 18th century, the Protestant gentry traded what remained of their independence for British security, and the 1800 Act of Union united Ireland politically with Britain. The formation of the Catholic Association by the popular leader Daniel O'Connell led to limited Catholic emancipation but further resistance was temporarily halted by the tragedy of the Great Famine (1845-51). The almost complete failure of the potato crop during these years led to mass starvation, emigration and death.

The bloody repercussions of the 1916 Easter Rising in Dublin added impetus to the push for Irish independence and in Britain's 1918 general election the Irish republicans won a large majority of the Irish seats. They declared Ireland independent and formed the first Dail Eireann (Irish assembly or lower house), under the leadership of Eamon de Valera, a surviving hero of the Easter Rising. This provoked the Anglo-Irish war, which lasted from 1919 to the middle of 1921. The Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921 gave independence to 26 Irish counties, and allowed six, largely Protestant, Ulster counties the choice of opting out. The Northern Ireland parliament came into being, with James Craig as its first prime minister. The politics of the North became increasingly divided on religious grounds, and discrimination against Catholics was rife in politics, housing, employment and social welfare. The south of Ireland was finally declared a republic in 1948, and left the British Commonwealth in 1949.

Instability in the North began to reveal itself in the 1960s and when a peaceful civil rights march in 1968 was violently broken up by the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC), the Troubles were under way. British troops were sent to Derry and Belfast in August 1969; they were initially welcomed by the Catholics, but it soon became clear that they were the tool of the Protestant majority. Peaceful measures had clearly failed and the Irish Republican Army (IRA), which had fought the British during the Anglo-Irish war, re-surfaced. The upheaval was punctuated by seemingly endless tit-for-tat killings on both sides, an array of everchanging acronyms, the massacre of civilians by troops, the internment of IRA sympathisers without trial, the death by hunger strike of the imprisoned and the introduction of terrorism to mainland Britain.

Political murals are a part of the North's urban landscape (21K)

Political murals are a part of the North's urban landscape (21K)

Northern Ireland lost its vestige of parliamentary independence and has been ruled from London ever since. The Anglo-Irish Agreement of 1985 gave the Dublin government an official consultative role in Northern Ireland's affairs for the first time. The jubilantly received ceasefire of 1994 was undermined by further murders, the reoccurrence of terrorism in Britain and the perceived intransigence of the British government in Whitehall. The mood shifted again with the election of Tony Blair in 1997 with a huge Labour majority to support him. The two sides resumed discussions and, in 1998, formulated a peace plan that offered a degree of self-government for Northern Ireland and the formulation of a North-South Council which would ultimately be able to implement all-Ireland policies if agreed to by the governments in Belfast and Dublin. As part of the plan, which was fully endorsed by a referendum, the South gave up its constitutional claim to the North. The whiff of peace is definitely in the air.

Figures refer to Eire only

GDP: US$45 billion

GDP per head: US$12,600

Annual growth: 7%

Inflation: 1.8%

Major industries: Computer software, information technology, food products, brewing, textiles, clothing

Major trading partners: UK, Germany, France, US

U2 may be Ireland's loudest cultural export, but of all the arts, the Irish have had the greatest impact on literature. If you took all the Irish writers off the university reading lists for English Literature the degree course could probably be shortened by a year. Jonathan Swift, Oscar Wilde, George Bernard Shaw, W B Yeats, Samuel Beckett and James Joyce are just some of the more famous names. Joyce is regarded as the most significant writer of literature in the 20th century, and the topographical realism of Ulysses still draws a steady stream of admirers to Dublin, bent on retracing the events of Bloomsday.

It's possible to add at least a couple of dozen more contemporary names to this heady brew, though it might be argued that the more spectacular highlights are JP Donleavy's The Ginger Man; Brendan Behan's Borstal Boy, Roddy Doyle's 1993 Booker Prize winner Paddy Clarke Ha Ha Ha, Patrick Macabe's brilliantly disturbing The Butcher Boy and anything with the word `peat' in it written by the poet Seamus Heaney.

As well as being a backdrop for all sorts of Hollywood schlock (Far & Away, Circle of Friends), Ireland has been beautifully portrayed on celluloid. John Huston's superb final film, The Dead, was released in 1987 and based on a story from James Joyce's Dubliners. Noel Pearson and Jim Sheridan's My Left Foot won Oscars for Daniel Day-Lewis and Brenda Fricker with the true story of Dublin writer Christy Brown, who was crippled with cerebral palsy. Lewis also starred in In the Name of the Father a powerful film telling the story of the wrongful conviction of the Guildford Four for an IRA pub bombing in England. Neil Jordan's The Crying Game is another depiction of the IRA, but with a sexual twist. Roddy Doyle's chuckly books lend themselves well to screen tales: The Commitments, The Snapper and The Van have all been filmed and his film Michael Collins depicts the life of the man who helped create the IRA.

Roddy Doyle's Dublin (23K)

Roddy Doyle's Dublin (23K)

Jigging an evening away to Irish folk music is one of the joys of a trip to Ireland. Most traditional music is performed on fiddle, tin whistle, goatskin drum and pipes. Almost every village seems to have a pub renowned for its music where you can show up and find a session in progress, even join in if you feel so inclined. Christy Moore is the king of the contemporary singer-songwriter tradition, traversing the whole range of 'folk' music themes and Moore's younger brother, Luka Bloom, is now carving out a jingly whimsical name for himself. Younger artists have their own takes on Irish folk, from the mystical style of Clannad and Enya to the sodden reels of the Pogues. Irish rock is always in amongst it, from Van the Man, Bob Geldof and crabby Elvis Costello to Sinéad O'Connor and The Cranberries.

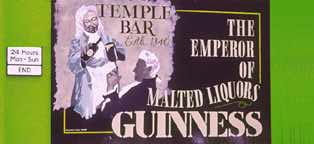

A Guinness in a pub: part of the compulsory Irish experience (27K)

A Guinness in a pub: part of the compulsory Irish experience (27K)

Although English is the main language of Ireland, it's spoken with a mellifluous lilt and a peculiar way of structuring sentences, to be sure. There remain areas of western and southern Ireland, known as the Gaeltacht, where Irish is the native language - they include parts of Kerry, Galway, Mayo, the Aran Islands and Donegal. If you intend to visit these areas, it would be beneficial to learn at least a few basic phrases. Since Independence in 1921, the Republic of Ireland has declared itself to be bilingual, and many documents and road signs are printed in both Irish and English.

Likely lads prove it's not all red hair and freckles in Ireland (19K)

Likely lads prove it's not all red hair and freckles in Ireland (19K)

Irish meals are usually based around meat - in particular, beef, lamb and pork chops. Traditional Irish breads and scones are also delicious, and other traditional dishes include bacon and cabbage, a cake-like bread called barm brack and a filled pancake called a boxty. The main meal of the day tends to be lunch, although black gold (Guinness) can be a meal in itself. If stout disagrees with you, a wide range of lagers are available. Irish coffee is not traditional, and is only offered in touristy hotels and restaurants, but the Irish drink lots of tea. When ordering whiskey, never ask for a Scotch. Ask for it by brand.

Many diverse events and festivals take place around the country over the year. February sees the Dublin International Film Festival. St Patrick's Day, 17 March, is a public holiday and that's about that - no parades, just the odd shamrock worn in a lapel. In the North, Easter is the start of the Orange/Protestant marching season. June 16 is Bloomsday in Dublin, with re-enactments and readings throughout the city. Listowel in County Kerry holds a Writers' Week literary festival during June, and there's a Jazz & Blues Festival in Belfast. July is when marching in the North really gets into its stride, and every Orangeman hits the streets on the Glorious 12th to celebrate the Protestant victory at the Battle of the Boyne.

Marches celebrate history but have also provoked violence (23K)

Marches celebrate history but have also provoked violence (23K)

August is horse-racing month, with the Dublin Horse Show and races in Tralee in County Kerry. In the same county, at Killorglin, the ancient Puck Fair heralds unrestricted drinking for days and nights. The first weekend in August is the date for Ireland's major annual rock festival, at Thurles in County Tipperary. In September Cork has its Film Festival and Belfast has a Folk Festival. In October, Dublin has its Theatre Festival, Ballinasloe in County Galway hosts the country's largest cattle and horse fair, and Kinsale in County Cork is home to Ireland's gourmet festival. In Wexford the November Opera Festival is an international event. Christmas is a quiet affair in the countryside though on 26 December the ancient practice of Wren Boys is reenacted, when groups of children dress up and expect money at the door after singing a few desultory hymns.

Visas:For citizens of most Western countries no visa is required. UK nationals born in Great Britain or Northern Ireland do not require a passport to visit the Republic

Health risks: None - the Catholic distaste for contraception does not prevent condoms being sold through pharmacies.

Time: GMT/UTC

Electricity: 220V, 50Hz

Weights & measures: Imperial and metric (see conversion table)

Tourism: 4 million visitors annually

Money & Costs

Money & Costs

Currency: Irish pound (or punt)

Exchange rate: US$1 = ú0.73

Relative costs:

- Budget meal: US$4-8

- Moderate restaurant meal: US$10-20

- Top-end restaurant meal: US$30 and upwards

- Budget room: US$10-20

- Moderate hotel: US$40-60

- Top-end hotel: US$70 and upwards

Ireland is expensive, but costs vary around the country. Assuming you stay at a hostel, eat a light pub lunch and cook your own meal in the evening, you could get by on US$25 a day. Once you factor in moving around the country, you'll need to increase your budget a bit. Added extras to watch out for include the awful practice of charging an extra pound or two for a bath and the more pleasurable ruin of buying the assembled company a round of expensive pints of Guinness.

Most major currencies and brands of travellers' cheques are readily accepted in Ireland, but carrying them in pounds sterling has the advantage that in Northern Ireland or Britain you can change them without exchange loss or commission. Banks generally give the best exchange rates, but change bureaus are open longer hours. Many post offices offer currency-exchange facilities and they're open on Saturday mornings. Credit cards are widely accepted, though many B&Bs and some smaller remote petrol stations will only take cash. There's quite a good spread of cash-spewing ATMs in the both the North and the South.

Fancy hotels and restaurants usually add a 10% or 12% service charge and no additional tip is required. Simpler places usually do not add service; if you decide to tip, just round up the bill or add at most 10%. Taxi drivers don't have to be tipped, but if you want to, 10% is fine. Tipping in bars is not expected.

The weather is warmest in July and August and the daylight hours are long, but the crowds will be greatest, the costs the highest and accommodation harder to come by. In the quieter winter months, however, you may get miserable weather, the days are short and many tourist facilities will be shut. Visiting Ireland in June or September has a number of attractions: the weather can be better than at any other time of the year, it's less crowded and everything is open.

Dublin

The Republic's capital, and its largest and most cosmopolitan city, Dublin makes a fine introduction to the country. It's a curious and colourful city of fine Georgian buildings, tangible literary history and extremely welcoming pubs, all on a scale that's very human. The city is bisected by the River Liffey, and is bounded to the north and south by hills. Most of the sights of interest are located south of the Liffey, which unlike most city rivers is a rural-looking stream with real fish living in it. The area to the north of the Liffey may be more run down than the south, but, according to Roddy Doyle, it's got more soul.

The Liffey's waters were once a vital constituent of Guinness (10K)

The Liffey's waters were once a vital constituent of Guinness (10K)

While heading south over the Liffey, you can't help but notice the huge white expanse of the 1780s Custom House on the northern bank, just one of Dublin's many fine Georgian buildings. Also on the north of the Liffey, the Four Courts were built by the same architect, James Gandon; their shelling in 1922 sparked off the Civil War. There are fine views of the city from the upper rotunda of the central building.

Trinity College is uppermost in the list of attractions south of the river. Founded by Elizabeth I in 1592, the university complex boasts a campanile and many glorious old buildings. Its major attraction, however, is the Book of Kells - an illuminated manuscript dating from around 800 AD, making it one of the oldest books in the world. The masterpiece is housed in the Library Colonnades. Other magnificent buildings include the imposing Bank of Ireland, originally built to house the Irish Parliament; Christ Church Cathedral, parts of which date back to the original wooden Danish church of the 11th century; and St Patrick's Cathedral, said to have been built on the site where St Patrick baptised his converts, and dating from 1190 or 1225 (opinions differ).

Another of Dublin's more obvious landmarks is its castle. More a palace than a fort, it was originally built on the orders of King John in 1204, although only the Record Tower survives from this original construction. One of the oldest areas of Dublin is the maze of streets around Temple Bar, now home to numerous restaurants, pubs and trendy shops. Dublin's fine museums include the National Museum, with an enviable collection of treasures dating from the Bronze Age onwards; the National Gallery, with particularly fine collections of Italian art; the Heraldic Museum, for those interested in tracing their Irish roots; and the Dublin Civic Museum. Dublin's fine Georgian buildings can be see to their best advantage from St Stephen's Green - a nine-hectare expanse of greenery right in the city centre. Other notable vantage points for spotting Georgian architecture include Merrion Square, Ely Place and Fitzwilliam Square.

Dublin has a wide range of accommodation possibilities, though it's wise to book ahead in summer. There's a congregation of hostels around O'Connell St, north of the Liffey, while the south side is given over to neater, cleaner (and more expensive) places. The area just north of the river is packed with restaurants of all types. The old, interesting and rapidly revitalising Temple Bar area, south of the Liffey, is Dublin's most concentrated restaurant area.

The Irish Republic's second largest city is a surprisingly appealing place - you'll find time passes effortlessly during the day, and by night the pub scene is lively. The town centre is uniquely situated on an island between two channels of the Lee River. North of the river, in the Shandon area, is an interesting historic part of the city, if a bit run down today. Sights to the south include Protestant St Finbarr's Cathedral, the Cork Museum (largely given over to the nationalist struggle in which Cork played an important role), the 19th century Cork Jail, the City Hall and numerous churches, breweries and chapels. Cork prides itself on its cultural pursuits, and apart from a heap of cosy pubs, the Cork Opera House, Crawford Art Gallery and Firkin Crane Centre offer both traditional and mainstream fare. A popular day trip from Cork is to Blarney Castle, where even the most untouristy visitor may feel compelled to kiss the Blarney Stone. Cork is around five hours to the south of Dublin by bus.

Waterford City

Waterford has a decidedly medieval feel, with city walls, narrow alleyways and a Norman tower - Reginald's Tower. Georgian times also left a legacy of fine buildings, in particular those on the Mall, a spacious 18th-century street. Important buildings include the 1788 City Hall (including a remarkable Waterford-glass chandelier) and the Bishop's Palace. The city's many churches are also noteworthy, in particular the sumptuous interior of Holy Trinity Cathedral. Waterford is first and foremost a busy commercial port city, situated on the River Suir whose estuary is deep enough to allow large ships to berth at the city's quays. The famous Waterford crystal is created 2km (1.2mi) out of town at the firm's factory. Waterford is in the south-east corner of Ireland; it is well serviced by both buses and trains.

Galway City

With its narrow streets, old stone shopfronts and bustling pubs, Galway is a delight. It's the west coast's liveliest and most populous settlement, and the administrative capital of County Galway. Its university attracts a notable bohemian crowd, and its boisterous nightlife keeps them there. Galway's tightly packed town centre lies on both sides of the River Corrib; most of the main shopping areas are east of the river. The Collegiate Church of St Nicholas of Myra, with its curious pyramidal spire, dates from 1320 and is Ireland's biggest medieval parish church. Its tombs are particularly noteworthy. Among the many interesting stone buildings are Lynch's Castle, a townhouse which dates in part back to the 14th century, and the Spanish Arch, which is about all that remains of the city's old walls. Galway's many fine cultural festivals include the February Jazz Festival, the Easter Festival of Literature and the Galway Arts Festival in July.

Belfast

Superficially, Belfast is a big, rather ugly industrial city dating in the main from only last century. But, of course, Belfast is not just any city - politics, history and religion are inescapable parts of its fabric. For visitors it is compact, with relatively light traffic and conveniently located points of interest. The major central landmark is Donegall Square, surrounded by imposing remnants of the Victorian era. It is in the west of the city that the poverty shows and that (Protestant) Shankill Rd and (Catholic) Falls Rd run - Six O'Clock News names if ever there were. Separate taxi services run tourists around the two mural-lined precincts for around ú10.

God, guns and (er?) liberation theology (23K)

God, guns and (er?) liberation theology (23K)

Donegall Square is dominated by the City Hall, a true example of muck-and-brass architecture. Also on the square is the Linen Hall Library, which houses a major Irish literary collection. The area north of High St is the oldest part of Belfast, and is known as the Entries. It was badly damaged by bombing during WWII, and today only a handful of pubs are left to reflect the character of the past. The River Lagan runs through Belfast, and the cranes of its shipyards still dominate the western skyline. Queen's Bridge, a lovely bridge with ornate lamps, is just one of those spanning the Lagan. The Crown Liquor Saloon displays Victorian architectural flamboyance at its most extravagant. As much a museum as hostelry, the Crown's exterior is covered in a million different tiles, while the interior is a mass of stained and cut glass, mosaics and mahogany furniture. It's impossible to get a seat, and even standing room is rare, but the Crown is well worth putting on your itinerary.

The Grand Opera House across the road is another of Belfast's great landmarks. It's been bombed several times, and at the moment has been restored in an abundance of purple satin. History and culture are on show at the Ulster Museum near the university; the collection includes items from the wrecked Spanish Armada of 1588. On the outskirts of Belfast are its splendidly located and well laid-out zoo; the Cave Hill Country Park; Belfast Castle, which dates in theory from the 12th century, but the existing structure was built in 1870; and Stormont, the former home of the Northern Ireland parliament, and now home to the Northern Ireland Secretary.

The bulk of Belfast's restaurants and accommodation cluster south of Donegall Square and along the inner-urban stretch known as the Golden Mile.

The River Foyle curves picturesquely around the old walled town of Derry, creating a cosy setting which jars horribly with the reality of this city's recent troubled history. The old centre of Derry is the small walled city on the west bank of the river, with the square called the Diamond at its heart. Barbed-wire barriers detract from the magnificence of the city walls, though also giving resonance to their history. From the top there are good views of the Bogside and its defiant murals - 'No Surrender!' - and the Free Derry monument. Inside the walls, the Tower Museum tells the story of Derry from the days of St Columcille to the present. St Columb's Cathedral stands within the walls of the old city and dates from 1628; it's usually surrounded by barbed wire and surveillance cameras. Last century, Derry was one of the main ports from which the Irish emigrated to the USA. The Harbour Museum has a small collection of maritime memorabilia on display. Derry is only just over one and a half hours from Belfast by bus.

The Burren

In northern County Clare, the Burren region is an extraordinary place. Miles of polished limestone karst stretch in every direction, and settlements along the coast are few; they include the popular Irish music centre of Doolin and the attractive coastal village of Ballyvaughan. Underground caverns, cracks, springs and chasms are the major features of the Burren, which is ringed by caves. Flora includes a bizarre mix of Mediterranean, Arctic and Alpine plants, and the region is the last bastion of the rare pine marten. In Stone Age times, the Burren was covered in soil and trees and supported quite large numbers of people. At least 65 megalithic tombs remain from this time; however, the vegetation was destroyed in this early version of land clearing, resulting in today's eroded limestone mass. Iron Age stone forts (known as ring forts) dot the Burren in prodigious numbers, and castle ruins add a touch of medieval mystery. Unpaved, green roads crisscross the region, reaching the most remote places; they date back many thousands of years.

Buses run to the Burren area from Limerick, Galway City and Ennis. Services in summer are fairly regular, but in winter you'd do well to plan your journey carefully to avoid getting stuck in a timetabling black hole.

Situated in County Offaly, this is Ireland's most important monastic site. It's superbly placed, overlooking the River Shannon from atop a ridge. It consists of a walled field containing numerous early churches, high crosses, round towers and graves. Many of the remains are in remarkably good condition and give a real sense of what monasteries were like in their heyday. The site is surrounded by low marshy ground which is home to many wild plants and bird life. The museum at the site exhibits graveslabs, original crosses and other artefacts uncovered during excavation. Clonmacnois is not serviced by public transport; the nearest town is Shannonbridge, 7km (4.3mi) to the south, from which you can hitch or take a taxi.

Connemara

The wild and barren region north-west of Galway City is known as Connemara. It's a stunning patchwork of bogs, lonely valleys, mountains and lakes, with only the odd remote cottage or castle hideaway for company. There's tremendous hill walking over the peaks of the Twelve Bens, which offer views over to the sea and its maze of rocky islands, tortuous inlets and sparkling white beaches. The coast road from the settlement of Spiddal meanders through the maze, but more unforgettable still is the journey through the Lough Inagh Valley and around Kylemore Lake - it would be hard to surpass the beauty of this landscape. Spiddal is only 17km (10.5mi) from Galway City, and is the gateway to these open landscapes and wild coastlines.

The perfect retreat for the quiet man, County Galway (23K)

The perfect retreat for the quiet man, County Galway (23K)

The three Aran Islands - Inishmor, Inishmaan and Inisheer - are long, low limestone moonscapes of bleak but rare beauty. They are home to some of the most ancient Christian and pre-Christian remains in Ireland; the massive Iron Age stone forts at Dun Aengus on Inishmor and Dun Conchuir on Inishmaan are of particular note. Almost nothing is known about the people who built these structures. Some of the earliest monastic settlements were founded here by St Eanna in the late 4th and 5th centuries; the remains surviving today date from the 8th century. The islands' isolation allowed Irish culture to survive when it had all but disappeared elsewhere. Irish is still the native tongue, and until recently people still wore traditional Aran dress.

The islands are criss-crossed by intricate stone walls, built over thousands of years and creating tranquil avenues of much-needed shelter from the wind. Inishmaan is the least visited island, while Inishmor is the most popular with day trippers. Inisheer lies closest to land, just 8km (5mi) from Doolin in County Clare. Ferries to the islands operate from Galway City, Rossaveal and Doolin.

Walking is one of Ireland's biggest attractions, and the country has miles of tailor-made walks. They include the Kerry Way, Beara Way, Ulster Way and Wicklow Way. It's a great way to open up the country and reach its most beautiful and fascinating corners. Cycling is another good way of getting away from the hordes, although some areas are prohibitively hilly. There are a number of excellent mountain-climbing opportunities, particularly Mt Gabriel (407m/1335ft) on the Mizen Head Peninsula, Hungry Hill (686m/2195ft) on the Beara Peninsula and Croagh Patrick (763m/2500ft) just outside Westport.

The coast of County Antrim: some of Ireland's best cycling (27K)

The coast of County Antrim: some of Ireland's best cycling (27K)

Ireland is renowned for its fishing, and many visitors come to the country just to cast a line. Permits are required (IRú5 a day), and a state national licence is required for salmon and sea trout. With a coastline measuring 5630km (3490mi), let alone its rivers and lakes, Ireland offers many opportunities for water sports. Good surfing spots include Easkey in the west of County Sligo, the Castlegregory Peninsula and Barley Cove on the Mizen Head Peninsula. The west coast offers some of Europe's best scuba diving, especially at Bantry Bay and Dunmanus Bay in County Cork, the Inveragh Peninsula in Kerry and around Hook Head in County Wexford. Sailing has a long heritage in Ireland, and the country has over 120 yacht and sailing clubs. The most popular areas for sailing are the west coast, especially between Cork Harbour and the Dingle Peninsula, the coastline north and south of Dublin, and larger lakes such as Lough Derg, Lough Erne and Lough Gill.

Virtually all international visitors to Ireland travel via England. There are flights between Dublin and Belfast and London's four international airports, as well as flights from British provincial cities. Several major European cities offer direct flights to Ireland. Airport departure taxes are built into the cost of your ticket. Ferry services between Ireland and Britain operate between Dublin and Holyhead in Wales; Rosslare and Fishguard and Pembroke, also in Wales; Belfast and Liverpool; and Belfast and Stranraer in Scotland. Services also link Cork with St Malo, Cherbourg and Le Havre in France.

Getting Around

Getting Around

The best way to see Ireland is by car, especially as many sights of interest are not served by public transport. However, car rental is expensive; in the high season it can often make good sense to arrange a package deal before you leave home. The Irish, like the British, drive on the left. Don't be fooled by Ireland's size: getting around by public transport is not as easy as you might like to think. Distances may be short, but in Ireland getting from A to B never follows a straight line. Rail fares are particularly expensive, there are notable gaps in the routes, and the frequency of both bus and train services can leave a lot to be desired. Winter bus schedules are drastically reduced, with many routes simply disappearing after September. Apart from Ireland's wealth of walking and hiking opportunities, cycling is a great way to get around - if you can ignore the hills, poor road surfaces and wet weather. Tourist offices all have regional cycling maps to help you plan your tour; West Cork in particular is ideal.

Recommended Reading

Recommended Reading

- For a readable and comprehensively illustrated short history pick up A Concise History of Ireland by Máire & Condor Cruise O'Brien or try The Oxford History of Ireland edited by RF Foster.

- Books about Northern Ireland's recent history tend to go out of date before they're published, and are rarely impartial. Free Ireland: Towards a Lasting Peace is Sinn Féin President Gerry Adam's latest, though David Thomson's enchanting memoir, Woodbrook, provides a more palatable slice of Irish history.

- Edna O'Brien's Mother Ireland is a lovely autobiographical travel book. Eric Newby's Round Ireland in Low Gear is a classic from the school of travel masochism. Newby pedals his way through lousy weather, steep hills, high winds and predatory trucks.

- If you're visiting Dublin, be sure to read Joyce's Dubliners or Roddy Doyle's Barrytown Trilogy. If you're heading off the beaten track to the Aran Islands, take JM Synge's The Aran Islands or Tim Robinson's Stones of Aran: Pilgrimage for company.

- See the culture section for a list of Irish writers renowned for spinning yarns.

- Culture Shock! Ireland by Patricia Levy is recommended as an up-to-date introduction to aspects of Irish culture.

- The Irish Pub Guide lists and describes a number of pubs across Ireland that are interesting for one reason or another.

Lonely Planet Guides

Lonely Planet Guides

Travellers' Reports

Travellers' Reports

On-line Info

On-line Info

Facts at a Glance

Facts at a Glance Environment

Environment

History

History Economic Profile

Economic Profile Culture

Culture Events

Events Facts for the

Traveller

Facts for the

Traveller Attractions

Attractions Off the Beaten Track

Off the Beaten Track Activities

Activities Getting There & Away

Getting There & Away Getting Around

Getting Around Recommended Reading

Recommended Reading Lonely Planet Guides

Lonely Planet Guides Travellers' Reports

Travellers' Reports On-line Info

On-line Info