| ||||||||||

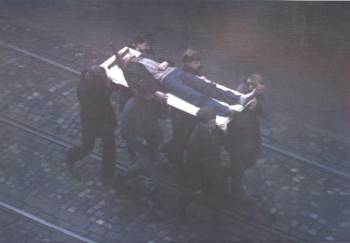

Czlowiek z zelaza [Man of Iron]

fot: Renata Pajchel |

At the Lenin Shipyard in Gdansk, talks between the government and workers had already been underway for some time, but at the beginning, only shreds of information were reaching Warsaw. At the time, the Association of Filmmakers, of which I was president, had won the right to record important historical events for archive purposes, and a group of filmmakers was already at the shipyard.

The workers' guard at the gate recognised me at once. While I was on my way to the assembly hall, one of the shipyard workers asked:

- Why don't you make a film about us?

- What kind of film?

- The Man of Iron - he answered without hesitation.

I had never made a film to order, but I could not ignore this call. The echo of Man of Marble returned to me; the final scene had ended right here, at the gates of the Gdansk shipyard. This could provide a good excuse for making a new film.

Obviously, it would be impossible to explain what had happened at the shipyard in 1980 without returning to the events of 1970 and showing the social protests on the Coast. Efforts made after 1970 by myself and others to show these events on the screen had not been succesful. Now, however, the authorities were considerably weaker, and the author of Man of Marble, Aleksander Scibor-Rylski, enthusiastically took to writing the script, while I, in my naivete, went to talk to General Jaruzelski about the tanks which I needed for filming the scenes of the state of emergency introduced in the Coast in 1970.

The film was created overnight despite enormous difficulties, particularly with the script. We were constantly learning about new things which should be included in the movie, while others, too obvious, had to be edited out. Fortunately, I was not alone. Agnieszka Holland helped me enormously, writing some of the scenes and dialogues, following the suggestions of the participants of those events, taking part in discussions which often lasted for several hours. In particular, the disclosures made by Bogdan Borusewicz proved to be exceptionally "filmworthy". We were learning to understand this new reality and to show it on the screen at the same time, which was not easy.

We had begun shooting in January 1981, and by June, in the company of Barbara Pec-Slesicka and Krystyna Zachwatowicz, I was on my way with a complete film via Stalowa Wola and Poznan to Gdansk.

Today I still feel a double satisfaction. In the first place, I had not shied away from the creative risks involved in dealing with current events, and secondly, I had managed to make the film before the imposition of martial law.

A few months later, Jaruzelski's tanks drove into the streets, confirming that the social contract had been signed under force... These were the same tanks which the general had refused to lend me for the film in the autumn of 1980.

Andrzej Wajda

Reviews

Man of Marble was a film about the past, even though it contained a contemporary plot whose heroine was Krystyna Janda.(...) Man of Iron has a deceptively similar form. Besides the contemporary theme, it contains some of the events of 1968, later of 1970, and still later, various sequences from the late seventies, preparing us for the outburst of 1980.

It is clear, though, that this time the entire structure is future-oriented. Both the genesis of the Polish August, and August events itself (shipyard strikes in Gdansk - translator's note) had become in the film not so much a reckoning with the present, but rather an opening into a future, fraught with danger and suffering, but nonetheless fascinating. What evidence do we have of this? Well, the exceptional, lightning tempo of the production of Man of Iron has been remarked upon universally, both in the sense of the creative concept and of the technical execution (although, as a rule, our film industry is not famous for its technical execution!). It seems that this tempo has transformed the social status of the film. It was not merely a demonstration of an attitude towards recent events. It was also an opportunity to incidentally influence the changes initiated by those events.

In contrast to Man of Marble, Scibor-Rylski and Wajda have undertaken an out and out hunt for facts. That is to say, archive photographs, tape recordings, documents, eyewitness testimonies, poster texts, graffiti, spontaneously composed songs. It is as if the creators felt embarrassed to use more sophisticated stylistic instruments, having thus avoided to remind us of the presence of an intermediary between the viewer and reality - talented perhaps, but always capable of deforming.

If I have described in detail the technique applied to enhance the flow of facts through fiction, it is not only because this has determined the style of the Man of Iron. It is also because this has been a successful undertaking in the domain of the most urgent experiments of today's cinematography, a domain in which, so far, we have had more fiascos than epic achievements. In awarding Wajda the "Golden Palm" the jurors at Cannes must have taken this into consideration, alongside with the social and moral arguments.

Jerzy Plazewski

"Kultura", Warsaw, 16 August, 1981

It is not surprising that Man of Iron has won the "Golden Palm". It has won unanimous praise for several reasons. The first of these is its perfection. The virtuosity of the Polish director in transforming the most burning current issues into a film masterpiece is another. And furthermore, this is a unique occasion. The fact that the Polish cinema could make such a statement at the Cannes festival is (perhaps) a guarantee of freedom. With the irony, so valued at Cannes, it has been said that Lech Walesa should have received the best actor award.

Jacqueline Carter

"France Soir", Paris, 28 May, 1981

The festival on the Cote d'Azur began in a heavily clouded atmosphere. Naturally, the organisers had to think of something to provide a particular political colouring. And so they prepared a "sensation"... The film Man of Iron by Polish film director Andrzej Wajda was included in the competition, although, contrary to tradition, it had not been viewed in its final version by any representative of the organizers... In short, the operation had been reasoned and worked out to the last detail. It was known in advance that Man of Iron was sure to win the first prize... We can now state with certainty that the decision of the jury was a purely political act. And this happened, above all, because Wajda's antisocialist film, made to serve the needs of political convenience, has all the features of a political pamphlet.

A. Kriwopalow

"Izwiestja", Moscow, 6 June, 1981

Wajda has never had to worry about the tricky business of presenting politics while making entertaining narrative cinema, and on the most superficial level Man of Iron exists as a technically polished, dramatically tense and moving moral tale. In another sense it offers the most succinct and compelling analysis of the background to the Polish upheaval.

Gustaw Moszcz

Sight and Sound, London, Autumn 1981

No, the "men of iron" in Wajda's film are not at all willing to assist (even in false forms) in the preservation of socialism; they are motivated rather by an absolute, unrestrained, and all-encompassing hatred.(...)

The utilitarian propaganda function of the film is so obvious that it is clearly only a political pamphlet, made with the purpose of strengthening the authority of the reactionary upper echelons of the union. They must be praised and at the same time defended against the grassroots criticism of the masses, who are increrasingly convinced that the sole aim of the "Solidarity" bosses is to intensify the crisis, to obstruct the efforts of the Party and the government to lead the country out of the impasse, and then to proceed to open confrontation with the nation. This would include exhortations to take over, change the constitution, withdraw Poland from the Warsaw Pact, as well as vulgar and vile insults directed against all socialist countries, especially against the powerful and loyal guarantor of Poland's national independence and of her socialist future - against the Soviet Union.(...)

Editorial Article

"Iskusstwo Kino", Moscow, October, 1981

This film is available at the Merlin bookstore

This film is also available at the www.amazon.com (with English subtitles)

Oscar | Films | Theatre | Why Japan?

Favourites | Pictures gallery | About Wajda | Bibliography

Main Page | Search | Wersja polska

Copyright © 2000 Proszynski i S-ka SA. All rights reserved