| ||||||||||

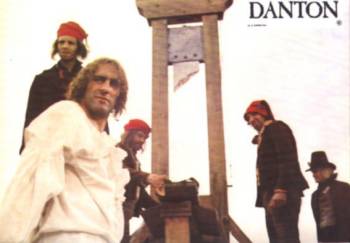

Danton

fot: Renata Pajchel |

Danton was produced on commission from Gaumont, and originally was to be produced in Poland. The imposition of martial law on the 13th of December, and the ban on gatherings of more than three people, made production in our country impossible. However, owing to Margaret Menegoz's enormous efforts, we were able to transfer the whole project to Paris, taking with us some of the Polish actors and a small group of co-workers.

On the streets of Paris, and in the historic interiors, the text of Stanislawa Przybyszewska immediately took on life and truth. Also, it rested on two strong pillars: the couple Depardieu - Pszoniak turned out to be infallible.

Before we began filming in Paris, while "Solidarity" was still functioning in Poland, GΘrard Depardieu came to Warsaw for one day to see the revolution, and especially, to see its leaders at the moment just before the collapse of their undertaking.

I wanted Depardieu to see the face of Revolution - inhumanly tired, with eyes wide open, suddenly falling asleep and never fully sleeping. Depardieu, guided by Krystyna Zachwatowicz, stood for a long moment in the hall of the Mazowsze Region headquarters with its endlessly milling crowds, where the history of those days was being created... No words and no director could have made a better jub of introducing GΘrard to the subject of my new film Danton than the scene which he saw with his own eyes.

Andrzej Wajda

Reviews

- As a historian, how did you react to Andrzej Wajda's Danton?

- I was very impressed with the dramatic intensity of the film, but I think that it takes too many liberties with historical reality. The logic of the revolution is very weakly presented, and there is no trace of the social forces which have driven those two sons of the revolution, Danton and Robespierre. I am under the impression that the film was conceived as a psychological study of the two characters. In this regard it is very Shakespearean, presenting the confrontation of two minds, two characters, two types of people. (...) I am really unable to recognise the personality of Robespierre in the Polish actor, even though he does humanise him. We don't see any evidence that Robespierre had to deal with discord among the revolutionaries, the la VendΘe uprising, and the dangerous war on the frontier. This was a man of the National Defence Committee, and therefore forced to be harsh, but he is remembered only as a man of the Terror. Even today Robespierre inspires fear. In Paris there is no Robespierre square or street.

Louis Mermaz

"La Croix", Paris,7 January, 1983

If the aim of this long film is to recreate only a few days, if in a film dedicated to the French Revolution we see only cabinet intrigues, personal rivalries, fanatic or terrorised politicians, mendacious or inspired speeches, it is done only to illustrate its main premise. In the spring of 1794 the counter-revolution was already suppressed, but the revolution, as later noted by Saint-Just, had been caught in a "frozen" state: the masses were uninterested, or even hostile, clubs had been closed, the public opinion was afraid. The Jacobinism of Paris sections had given way to Jacobinist committees - mainly those of Public Salvation and Security - where Robespierre has a decisive influence. That is why Wajda shows the "people" only in the form of long queues at the doors of a bakery.(...) The film has respected the time of the events, but it is a film without society and without people. The revolution becomes a theatre of a dozen or so characters who second - or rather view - the duel of the principals, trying to guess who will be the winner. The film recreates, with ubelievable clarity, the dominant feeling experienced by all the great actors of the revolution - that history is unfolding above them rather than through them.

Franτois Furet *

"Le Nouvel Observateur", Paris, January, 1983

* French Revolution historian

Andrzej Wajda's Danton invaded the "ZooPalast" and demonstrated to the Berlin audience a perfect union of film art and politics. For a film which has been raked over the sharp critical coals by two horses as different as the French Communist Party and the Hollywood industry magazine "Variety", its merits came as a real surprise. The film is a masterpiece of dramatic historical cinema and anyone with eyes to see should take the trouble to open them widely. (...) "We are the last chance for freedom" - says Danton. Wajda's film convinces us how terribly fragile freedom is. Anyone who doubts this should go to see the Berlin Wall.

Harlan Kennedy

"Film Comment", New York, May-June 1983

Led by Wajda's sure hand, the direction transformed that which might have been a wordy political dialectic into breathtaking cinema. (...) Wajda does not declare a decisive verdict on the subject of the battle between moderation and extremes. The tempo of revolutionary change is so intense that there is probably no way that an individual or even a political party can resist it. Even the pressure of the masses is incapable of deterring the guillotine. Neither Danton's pragmatism nor Robespierre's idealism are of any use. This is the gloomy lesson, which Wajda extracts from 18th century French history. It is more than likely that it can be applied to his own country today.

J.K.

"Newsweek", New York, 24 January, 1983

Oscar | Films | Theatre | Why Japan?

Favourites | Pictures gallery | About Wajda | Bibliography

Main Page | Search | Wersja polska

Copyright © 2000 Proszynski i S-ka SA. All rights reserved