| ||||||||||

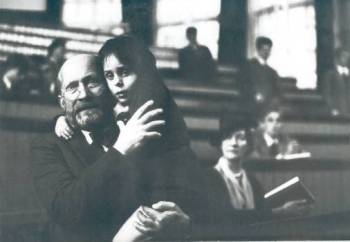

Korczak

fot: Renata Pajchel |

I think that I commited to Dr. Korczak all of my talents and skills, although the shooting of the film coincided with the 1989 election, which for me involved almost daily presence in the Senate.

The official screening at Cannes during the 1990 festival, folowed by the standing ovation in the Festival Palace was, regrettably, the last success of Dr. Korczak.

By the next morning, the review in "Le Monde" had tranformed me into an anti-Semite, and none of the major film distributors would agree to circulate the film outside Poland.

My good intentions were useless.

Andrzej Wajda

Reviews

Wajda returns to Cannes with a film full of that strength which we love so much.(...) The flawless script by Agnieszka Holland, the black-and-white photography, amazingly intensifying the cruellest details of life in the ghetto, and signed by Robby Mⁿller (cameraman for Wim Wenders and Jim Jarmusch), Wojciech Pszoniak's interpretation, full of dignity, gives this battle for humanity the magnitude it call for.(...) Respect, that is the word which spontaneously comes to mind.

Jean Ray

"L 'Humanité", Paris, 12 May, 1990

The profound indifference of the Polish filmmaker makes me shiver. At no point during the film does one sense emotion, even in intention. Why are these children denied not only their history, but also their suffering and despair, which are totally absent from the screen?

Anne de Gaspieri

"Le Quotidieu", Paris, 12 May, 1990

After delight û disgust, like at every great festival. Remain calm, don't get excited, and just say no. No, to Dr. Korczak, a film by Andrzej Wajda.(...) The film is well made, since Wajda, the "man of lead," is a competent craftsman. It is filmed in black-and-white, with a few hidden inserts from old film news to lend verisimilitude. One could almost believe it. But there is no need for all this; despite the overwhelming dexterity pervading the film, a real hero of such charismatic intensity inescapably draws us into the overall illusion of truth.(...) And what do we see? Germans (brutal, they must be brutal) and Jews, in collaboration. Poles - none. The Warsaw Ghetto? A matter between the Germans and the Jews. This is what a Pole is telling us. The embarrassment which accompanies us from the start of the showing changes into distaste. Until the epilogue, which almost makes us faint.

The deportation orders are signed. The liquidation of the ghetto is underway. Under the Star of David, the children and Dr. Korczak enter the sealed carriage singing. And then the doors swing open - a coda to a sleepy, disgusting dream on the edge of revisionism - and we see how the little victims, energetic and joyful, emerge in slow-motion from the train of death. Treblinka as the salvation of murdered Jewish children. No. Not at the moment of profanation of the Jewish graves in Carpentras. Not ever.

DaniΘle Heymann

"Le Monde", Paris, 13 May, 1990

The question, which takes precedence over all others: does a non-Jew have the right to touch on "purely" Jewish matters? This must be answered at once, and honestly: to claim that a non-Jew has no right to create a work about Shoah, is practically the same as saying that Korczak knew nothing about childhood because he did not have children of his own. Extermination struck out at Jews and Gypsies, but it concerns the entire human race. To deny a non-Jew the story of Korczak is to be responsible for restricting the significance of the catastrophe to those affected by it, and to desist from urging people that they be aware of the irrevocable harm the camps, transports in sealed carriages, and lethal gassing have done to humanity.(...)

It is said that the filmmaker and his scriptwriter, Agnieszka Holland, have transformed a Jewish doctor into a saint, Catholic and Polish. We must repeat again and again that Korczak was profoundly Polish; before the war he accepted into his orphanage both Jewish and non-Jewish children. What's more, his concept of children's rights, even though based on time-honoured principles of justice and compassion, has remained alien to Judaic tradition. (...)

The most surprising thing, since it comes from a director with a hastily fabricated anti-Semitic reputation, is the way he shows a cabaret and the collaborating businessmen in the ghetto. In this scene, as well as at other moments, we observe a young Jew, an honourable gangster, from whom Korczak neither distances himself nor gives him lectures on morality. We see this person in the ending, as the carriages are being loaded, when for the last time he attempts to persuade the man he loves and admires to escape. But returning to the cabaret: the almost Dionysian moment of Yiddish songs, circulating banknotes and flashing jewellery, can only be regarded as anti-Semitic by those who think all Jews are angels, to whom the ghetto is a sacred place, and who do not know that in this community, in the midst of death, life went on unceasingly.(...) Wajda's Dr. Korczak, and even more so Rymkiewicz's Umschlagplatz might be the first signals of a Polish-Jewish symbiosis which would be the Nazis' final defeat.

Elisabeth de Fontenay

"Messager Européen"

Those critics who detect only a Christian vision in the final ethereal scene (Korczak and the children leap off the train in slow-motion and fade into a misty countryside) are unfair to Wajda. After the war there were rumours that the carriage with the transport from the orphanage became miraculously unlinked from the train. Villagers throughout Poland recognised the "old doctor" and his children. It could be that, like Wajda, they wanted to believe that people like Korczak are indestructible. What a shame that Wajda was unable to accomplish his original idea of making a Polish Doctor Zhivago, showing Korczak's pioneering work in the field of children's tribunals, children's rights, and moral education. Instead of stirring up Polish-Jewish antagonisms, we should rather be thankful for the sincere sympathy with which Wajda attempts to recreate this modern Jewish hero who died - like he lived - for his children.

Betty Jean Lifton*

"The New York Times", New York, 5 May, 1991

* Author of the Korczak biography The Children's King.

This film is available at the Merlin bookstore

This film is also available at the www.amazon.com (with English subtitles)

Oscar | Films | Theatre | Why Japan?

Favourites | Pictures gallery | About Wajda | Bibliography

Main Page | Search | Wersja polska

Copyright © 2000 Proszynski i S-ka SA. All rights reserved