| ||||||||||

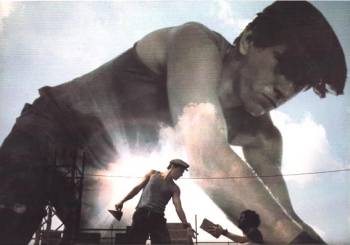

Czlowiek z marmuru [Man of Marble]

fot: Renata Pajchel |

In 1962, I began to consider a contemporary film addressed to the Polish audience. I needed to discuss this subject with others.

Jerzy Stawinski and Jerzy Bossak, whose impact on the Polish cinema of that time was enormous, were fantastic discussion partners. After a short while, I found an appropriate subject. It all began with a minor anecdote, which Jerzy Bossak had read in a newspaper: A brick-layer had come to the employment office, but he was not given a job because Nowa Huta (a steel mill near Cracow - translator's note) now needed workers only for the foundry. One of the clerks, however, remembered the man's face. Yes, he was a well known "labour leader", a brick-layer and an ex-star of the previous political season.

It was not much to begin with, but our art director knew who could write a script based on this incident. Scibor-Rylski had been the scriptwriter for Ashes, and I knew that he had written a socrealist novel which I had never even tried to read; I didn't know, however, that he had also written profiles of several famous brick-layers for the so called "Library of Leaders of Labour."

Bossak and Scibor used to be journalists and were familiar with the problem of labour leaders both from the official ideological standpoint and from conversations with the workers themselves, who hated this "labour race." We only needed an generating idea for the future film. Scibor was then on his way to Zakopane, so I wrote a letter to him in which I attempted to elaborate on Jerzy Bossak's anecdote.

The labour leader, a bricklayer, was a hero of that period, the fifties. But I was looking for a contemporary subject, so I needed a agent through whom I would be able to tell the whole story from today's perspective.

Of course, it had to be a young person, for whom the era of stalinism would belong to the distant past. Among the many talented students of the Lodz Film School was Agnieszka Osiecka. And that is how I got the idea: Agnieszka, a young student of the film school, would try to uncover the mystery of the bricklayer's life.

A few weeks later the script was ready; I read it feverishly. I knew I had a golden apple in my hands. Unfortunately, this was where my initiative ended - from now on all depended on the Script Commission, or, precisely speaking, on the propaganda department of the Central Committee, as the subject of labour leaders touched upon the most embarrassing aspect of the socialist economy, namely, the steadily decreasing labour effectivity.

We managed to publish the script in the Warsaw weekly Kultura on 4 August, 1963, and Scibor believed that we had overcome at least one obstacle - censorship of the press. Unfortunately, many "comrades", who wanted to demonstrate their Party alertness, had read our text and, as a result, the script had been banned for many years. Of course, no one even mentioned its cinematic value.

Fourteen years passed. What follows sounds like a fairy-tale, but it was true. The generally hated Gomulka was deprived of his position as First Secretary, taking the cult of the fifties with him. His successors were younger politicians, former ZMP members, and we began negotiations with them from scratch.

Jozef Tejchma took full responsibility for Man of Marble, and it is only owing to his influence that the film was made and, more important, released.

In spite of protests from various rungs on the decision-making ladder, Man of Marble was released. The audience did the rest. The only thing which I didn't even dream of was that my film would represent Polish cinema at some film festival. But here, again, chance came to my aid. The Paris distributor of my films, Tony Molière, bought Man of Marble and was sent a copy for adaptation. In this way, the director of Cannes festival, M. Jacob, could view the "banned" film in Paris and include it in the festival program, although not in the competition, as a Surprise Film.

Andrzej Wajda

Reviews

First, I tried to get into a screening at the "Wars" cinema, without success. On Friday night, someone called me, very excited, and said that the film was to be screened at three other cinemas. In the morning, the door-bell rang û it was a neighbour with whom I exchanged good mornings in the forecourt. She said: "By the box-office at the 'Wisla' movie theatre some nice young men are compiling a list of those who want to see the film. Hurry up." I was sixtieth in this strange community of people who wanted to see Man of Marble, and who wanted it more passionately than the usual film-fans. (...)

In Birkut, a labour leader from Nowa Huta (...) I recognised my own generation with its black-and-white faith (just like on the screen), enthusiasm and naivete, with its, not yet anticipated, susceptibility to later disillusionment and defeat; I had been there, I had unloaded bricks at night at the Nowa Huta railway siding, worked my way through mud, slept in a big hall with the members of the young men's work brigade, written about them a poem as primitive as they were, and read it aloud in the light of a weak electric bulb. (...) I am recollecting all this not because I feel sentimental about our youth; I think about it - in life and on film - with mixed feelings, which involve sentiment but also painful self-irony, shame, bitterness... So, is this a renaissance of Polish film? Perhaps not only of film?*

Wiktor Woroszylski

"Wiez", Warsaw, May-June, 1977

* The censors deleted the two last sentences.

The script, which was written many years ago, is inflated and its reckoning with the past unnecessarily rankles; we did not reject the past then and do not reject it now. (...) The impression we get is of a construction which is internally unbalanced and conclusions which are not always justified and based on tenuous premises.

Wojciech Wierzewski

"Trybuna Ludu", Warszawa, 4 March, 1977

I have found in this film a piece of splendid journalism. It communicates so much that an army of Western correspondents would not be able to gather this information. My belief that didactics and aesthetics in film should be separated of has been shattered. This is an experience so rare in today's cinema that this film should be spared any critical remarks.

Franz Manola

"Die Presse", Vienna, 20 September, 1980

Wajda's synthesis has given birth to an outstanding art work about revolt against submission. Historical limitations are recognised, but people don't have to wear masks or have double standards any longer. Passionate and driven by the desire for a harmonious life, Man of Marble is an exceptional drama about the revolt of flesh, blood and common sense in defence of the right to authenticity, naturalness, and spontaneity. This is not nihilism - to the contrary, it is life û lived with the awareness that such a way of living is the most free, and the most moral.

Sveta Lukic

"Borba", Belgrade, 24 February, 1979

The originality of Andrzej Wajda's film Man of Marble lies in the fact that it is not original (what can be less original than the fate of a labour-leader from the stalinist era?).

The beauty of this exceptional film lies in the complexity of the director's attitude towards Birkut, a representative - perfect in his submissiveness - of the whole miserable, alienated period. Wajda wants to communicate two opposing truths: first, that stalinism was a disaster and second, that the people who believed in it û and whom it consequently crushed û were driven by an honest spirit of idealism. It hasn't been easy to juxtapose these two messages, but Wajda has succeeded completely. Like every artist worth his name, he began not with the typical, but with the individual. Before Birkut became a lead labourer he possessed all the virtues and vices which have always been a constant element of humanity, regardless of place and time. Disguised by the label of socialist hero were humility and decency û qualities which made him a real hero. What was the effect of this delicate operation? Stalinism has been unconditionally condemned, but socialism as an idea and utopia seems to be saved.

The film is strictly consistent in form, which leaves no room for sentimentalism, so easy to introduce. The action takes place among the bare walls of the shipyard and office buildings, and it draws us in like a detective story, one, however, in which we don't search for the criminal but for historical truth. The only feeling is one of regret that the problems, which caused so much suffering in the past, have not been fully solved.

Alberto Moravia

"L'Espresso", Rome, 29 April, 1979

For nearly two months Man of Marble has again been screened, and the movie theatres are full. Even though two and a half million people have already viewed the film, Andrzej Wajda's name has been covered with mud. This has been the biggest press campaign in the last decade directed against an individual artist, a campaign that became a test of courage and decency. The attitude towards this campaign clearly divided critics, journalists, and activists, while decent people were found in unexpected places. Especially so, as defending the film was almost an act of heroism and some people lost their jobs in the result. So when journalists presented their award to Wajda at the Gdansk Film Festival in 1977, the censors office banned all mention of the fact and the honorary brick could only be awarded to the prize-winner on the stairs of the festival building. (...)

Andrzej Wajda had carefully balanced historical and moral arguments. At one end of the scale he put human fate, at the other - material progress, but he didn't say which side "weighed" more. He presented a certain story but left room for different evaluations. It was precisely this objective attitude that caused such a furious outcry. This witch-hunt directed against an artist revealed the fear of the hunters. They did not want a public debate about the origins of their power, because they were afraid of losing it. They were leading the country to disaster and three years later they lost their power in disgrace, thus indirectly proving Wajda had been right.

Krzysztof Klopotowski

"Literatura", Warsaw, 23 October, 1980

This film is available at the Merlin bookstore

This film is also available at the www.amazon.com (with English subtitles)

Oscar | Films | Theatre | Why Japan?

Favourites | Pictures gallery | About Wajda | Bibliography

Main Page | Search | Wersja polska

Copyright © 2000 Proszynski i S-ka SA. All rights reserved