White Dwarfs

Introduction to White Dwarfs

Where a star ends up at

the end of its life depends on the mass, or amount of matter,

it was born with. Stars that have a lot of mass may end their lives as

black holes or

neutron stars.

Low and medium mass stars will become something called a white dwarf.

A typical white dwarf is half as massive as the Sun, yet only slightly

bigger than the Earth. This makes white dwarfs one of the densest forms of

matter, surpassed only by

neutron stars.

|

|

|

| Black Hole |

Neutron Star |

White Dwarf |

Medium mass stars, like our Sun, live by burning the hydrogen that dwells

within their cores, turning it into helium. This is what our Sun is doing

now. The heat the Sun generates by its nuclear fusion of hydrogen into

helium creates an outward pressure. In another 5 billion years, the Sun will

have used up all the hydrogen in its core.

This situation in a star is similar to a pressure

cooker. Heating something in a sealed container causes a build up in

pressure. The same thing happens in the Sun. Although the Sun may not

strictly be a sealed container, gravity causes it to act like one, pulling

the star inward, while the pressure created by the hot gas in the core

pushes to get out. The balance between pressure

and gravity is very delicate.

When the Sun runs out of hydrogen to burn, gravity temporarily tips the

balance, and the star starts to collapse. But compacting a star causes

it to heat up again and it is able burn what little hydrogen remains

in a shell wrapped around its core.

January 15, 1996,

Hubble Space Telescope

Captures First Direct

Image

of a

Star, A. Dupree (CfA)

and NASA.

|

This burning shell of hydrogen will give our Sun the energy to expand again.

When this happens, our Sun will become a red giant; it will be so big that

Mercury will be completely swallowed!

When a star gets bigger, its heat spreads out making its overall

temperature cooler. But over time, the core temperature of our red giant Sun

will increase again until it's finally hot enough to burn all the stored up

helium it created in its former incarnation. Eventually, it will transform the

helium into carbon and other heavier elements. The Sun will only spend one

billion years as a red giant, as opposed to the nearly 10 billion it spent

busily burning hydrogen.

|

We already know that medium mass stars, like our Sun, become red

giants. But what happens after that? Well, our red giant Sun is still

eating up helium and cranking out carbon. But when it's finished its

helium, it isn't quite hot enough to be able to burn the carbon it created.

What now?

Our Sun isn't hot enough to ignite the carbon it its core, so the only

thing it can do is succumb to gravity again. When the core of the star

contracts, it causes a release of energy that makes the envelope of the

star expand. Now the star has become an even bigger giant than before!

Our Sun's radius has become larger than Earth's orbit!

The Sun is not very stable at this point and loses mass similar to how

a boiling kettle loses water by releasing steam. This continues until

the star finally blows its outer layers off in a gust of superwind.

The core of the star, however, remains intact, and becomse exposed to

the outside universe -- this is the white dwarf. This leaves behind a

white dwarf surrounded by an expanding shell of gas in an object known

as planetary nebula. They

are called this because early observers thought they looked like the

planets Uranus and Neptune. There are some planetary nebulae that can

be viewed through a backyard telescope. In about half of them, the

central white dwarf can be seen using a moderate sized telescope.

Planetary nebulae seem to mark the transition of a medium mass star from red

giant to white dwarf. Stars that are comparable in mass to our Sun will

become white dwarfs within 75,000 years of blowing their envelopes.

Eventually they, like our Sun, will cool down, radiating heat into

space, fading into black lumps of

carbon. It has taken 10 billion years, but our Sun has reached the end of the

line and quietly become a black dwarf.

White dwarfs can tell us important things about the age of the universe.

If we can estimate the time it takes for a white dwarf to cool into a

black dwarf, that would give us a lower limit on the age of the universe

and our galaxy. Because it takes billions of years for white dwarfs to

cool, we don't think the universe is old enough yet for many, if any,

white dwarfs to have become black dwarfs. This is why we want to learn

more about white dwarfs. They could be an important key to understanding

our universe.

Observations of White Dwarfs

|

There are several ways to observe white dwarf stars. The first white

dwarf ever to be discovered was found because it is a companion star to

Sirius, a bright star in the constellation Canis Major. In 1844, astronomer

Friedrich Bessel noticed that Sirius had a slight back and forth motion,

as if it were being orbited by an unseen object. In 1863, this

mysterious object was finally resolved by optician Alvan Clark. This

star was later determined to be much small ther Sirius itself - that

is, a white dwarf. This pair are now referred to as Sirius A and B, B,

being the white dwarf. The orbital period of this system is about 50

years.

Since white dwarfs are very small and thus very hard to detect, binary

systems are a helpful way to locate them. As with the Sirius system, if a

star seems to have some sort of unexplained motion, we may find that the

single star is really a multiple system. Upon close inspection we may

find that it has a white dwarf companion.

|

The arrow is pointing to white dwarf, Sirius B.

|

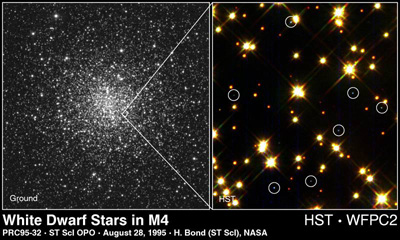

The Hubble Space Telescope, with its 2.4

meter mirror and advanced optics,

has been successful at viewing white dwarfs with its Wide Field and

Planetary Camera. In August of 1995, this camera observed more than

75 white dwarfs in the globular cluster M4 in the constellation

Scorpius. These white dwarfs were so faint that the brightest of them

was no more luminous than a 100 watt light bulb seen at the moon's

distance. M4 is located 7,000

light years away, but

is the nearest globular cluster to Earth. It is also approximately 14

billion years old, which is why so many of its stars are near the end

of their lives.

|

Optical Image (left) and a portion of the Hubble Space

Telescope observation (right) of the globular cluster M4. The

white dwarfs are circled in the HST image.

|

|

Optical mirrors are not the only way to view white dwarfs. The white

dwarf HZ 43 was observed by the X-ray satellite ROSAT. In normal stars

the photosphere (the visible surface of the star) is too

cool to emit X-rays. When such stars emit X-rays, they are

actually from the corona,

a region surrounding the photosphere filled with very tenous gas

having a temperature of 1 - 10 million degrees. X-rays from the white

dwarf stars are different. Here, X-rays come from slightly inside the

visible surface, which is very dense and can be as hot as 100,000

degrees in a very young white dwarf star.

A white dwarf's helium and hydrogen outer layers are thin, and are

essentially transparent to the X-rays that are emitted by the much hotter

inner layers.

|

ROSAT image of HZ 43

|

Last Modified: November 2004

The above images of Betelgeuse and M4 were created with support to Space

Telescope Science Institute, operated by the Association of Universities

for Research in Astronomy, Inc., from NASA contract NAS5-26555, grant number

STScI-PRC96-04, and are reproduced with permission from AURA/STScI.

The two planetary nebulae images are courtesy of

Bruce Balick and Jay Alexander, University of Washington,

Arsen Hajian, U.S. Naval Observatory,

Yervant Terzian, Cornell University,

Mario Perinotto and Patrizio Patriarchi, Observatorio Arcetri (IT)

The image of Sirius A and B is courtesy of Lick Observatory.

|