| ||||||||||

L'amour à vingt ans [Love At Twenty]

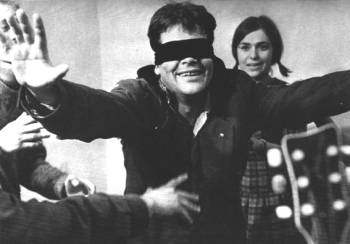

fot: Renata Pajchel |

An aspiring French producer Pierre Roustang, who had recently made a film with Barbara Kwiatkowska (or rather, Barbara Lass), arrived at an idea to produce a collection of film stories on how "love looks today in different parts of the world". He planned his film as a collective portrait of the younger generation, and filmmakers from France, Germany, Italy, Japan and Poland were invited to take part.

In spite of such uncertainties, I finally managed to find the right subject and, even more important, a part for Cybulski. I happened to hear a true story, which allegedly was reported by a Wroclaw newspaper. In the Zoo, a man rescued a child who somehow got into the polar bears' enclosure. The girl was unharmed, but her savior melted unseen into the crowd of alarmed spectators. So much for the facts.

I knew that nobody but Zbyszek Cybulski could play the part. Zbyszek had changed since Ashes and Diamonds; he was heavier now, and had lost his boyish looks. But after all, he was to play an older, unappreciated hero, who had survived the war only to stagnate in anonymity. After dealing with the lost war in Lotna and in Kanal now came the time to tackle the theme of pointless lives.

I was happy to work with Zbyszek again, who also felt this was his chance to play an important role. Dressed in an old tight coat and a beret, and riding a battered bicycle, he came to embody the average man in the street, living a life without expectations.

Andrzej Wajda

Reviews

At the end of this novel film, which requires sitting through a lengthy "no man's land", is an interesting Polish episode by Andrzej Wajda about the impassable abyss between those who remember the war, and those who do not. The man reading the gas meters, played by Zbigniew Cybulski, faints while playing blindman's bluff because it reminds him of the time when the Nazis put him up against the wall to shoot him. The young people accept as obvious that he is drunk. This is too large a subject to be presented in such a brief episode. The director begins the film with a typically Polish bravura scene in which a polar bear attacks a child at the zoo. I presume that this can succeed so well only for a director with the characteristic Polish mix of black sophistication and baroque romanticism.

The Observer, London, 20 September 1964

After oscillating for two long hours between suspicions inspired by Truffaut's misogyny; the overpowering tedium of Ophⁿls' work; and the cheap jokes of Rossellini jr. who in his stupidity and sloppiness managed to surpass even his own father; after surviving these hardships, barely relieved by the clumsy and highly affected piece of Japanese necrophila, the patient viewer is finally rewarded with the final episode, signed by Andrzej Wajda... In what could have become a tired repetition of the "eternal" conflict between the younger and older generations, or, worse still, a vicious pamphlet against today's youth, Wajda has miraculously achieved a penetrating sense of balance. Instead of extolling the heroism of the former underground fighter as opposed to the superficiality of the current reality, or exiling his opponents to the twilight of historical fatalism, he has had the courage to confront both parties, i.e., to show the genuine bravado, but also the silly complacency of the man whose days are over, on the one hand, and the instinctive cruelty of the young, but also the girl's clumsily genuine tenderness... Mastery instead of silly jabbering, penetration instead of muddled obsessions: living proof, four to one - which could win even against a hundred - of how empty our nouvelle vogue really is.

Louis Seguin

Positif, Paris, December 1962

Oscar | Films | Theatre | Why Japan?

Favourites | Pictures gallery | About Wajda | Bibliography

Main Page | Search | Wersja polska

Copyright © 2000 Proszynski i S-ka SA. All rights reserved