Road

warrior

¼r≤d│o:

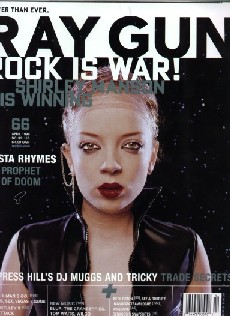

Ray Gun kwiecie±'99

Shirley Manson

loathes female power but loves female equality. Natalie Nichols

joined the Garbage queen for a lap on the touring treadmill.

With her high-riding crimson

ponytail and ultra-mod black eye makeup, Shirley Manson looks

like she just dropped in from some exotic planet. But when she

speaks, the siren of Garbage is unmistakably, delightfully human.

"I'm starving," she announces in a melodious Scottish

lilt. Her face is flushed from the chill wind of this deceptively

sunny Boston day. Settling at a nearby table in the hotel

restaurant, she talks about the photo shoot she's just finished.

"I have to get something to eat," she tells her

publicist. "But then I want to talk to you about

something."

With her high-riding crimson

ponytail and ultra-mod black eye makeup, Shirley Manson looks

like she just dropped in from some exotic planet. But when she

speaks, the siren of Garbage is unmistakably, delightfully human.

"I'm starving," she announces in a melodious Scottish

lilt. Her face is flushed from the chill wind of this deceptively

sunny Boston day. Settling at a nearby table in the hotel

restaurant, she talks about the photo shoot she's just finished.

"I have to get something to eat," she tells her

publicist. "But then I want to talk to you about

something."

"Something has

nothing to do with this stop on the Version 2.0 tour, just one

more hectic day-in-the-life, which will culminate in Garbage

opening for Hole at the historic Orpheum Theatre, the crowning

event of alternative station WBCN-FM's annual holiday music

festival. She briefly raves about how ell the video shoot for the

album's fourth single "When I Grow Up," has been going,

but what she really wants to discuss are Marilyn Manson's latest

alleged antisocial antics.

Ms. Manson chooses the

lunch buffet. "Instant gratification, "she quips. She's

back in a flash with her selections including rolls and tuna

salad. "Give me your butter, your mustard, and your

mayonnaise," she barks. We snatch them off our table and

shove them her way. "Thank you," she purrs, accepting

them regally. "Now carry on."

In the four years since

she rose from obscurity to become the much-celebrated sex-bomb

mouthpiece for one of the decade's most innovative rock bands,

the 32-year-old singer/producer has admitted to more obsessive

behavior than most human beings ever would, let alone most pop

stars. All day, she will fret about how she looks on various

magazine covers. But she hasn't a clue why any star [star such as

her namesake Marilyn] would resort to violence over his or her

image in the media. "It's ludicrous to care that much,

"she sensibly remarks.

Shirley doesn't believe

in violence, unless someone's really asking for it. Then she

doesn't think twice about using any resource at her disposal.

Like a few months earlier, on stage at the Hollywood Palladium in

Los Angeles, when she reflexively threatened an unruly fan with

mayhem. "Do that again, and I swear I'll find you!" she

screamed , promising to have security tear the perpetrator limb

from limb.

"Somebody threw

something at me, and I kind of lost my temper," she recalls

later, backstage at the Orpheum a couple of hours before

showtime. "For me to rage at somebody when I'm up on a

stage, and they're in the middle of a crowd where I can't find

them, is ludicrous. But the idea of 20 security men coming for

you is kind of scary."

She is finishing up her

makeup, painting her lips a bright magenta. Only moments before I

had been trying to eavesdrop while she talked with her publicist

about yet another cover photo, and instead found myself in the

narrow hallway, face-to-face with drummer Butch Vig, who casually

introduced himself along with his fellow producers and Garbage

guitarists Steve Marker and Duke Erikson.

SUPERVIXEN

The Orpheum dressing room is so tiny, the treadmill she

travels with is taking up half the space. "I exercise for my

mind, not my body," she explains matter-of-factly. The

remaining area is strewn with clothes, magazines, a big silver

makeup case, CDs, and a boombox. She's dressed for the workout

she'll son be getting onstage: black cargo pants, black tank top

with a yellow diagonal stripe, skinny leather dog collar. Amber

sequins glitter along the French braid that runs along the top of

her head.

Usually, she says, the

only weapon she needs to control boisterous fans is righteous

fury. Even when an audience member once snatched her wedding ring

from her hand, she only had to rage, "Somebody out there's

got a ring of mine, and I want it back. And I want it back RIGHT

NOW!" She was trying to be subtle, she says, to ensure the

culprit would hand over the precious item. "I knew that if I

said it was my wedding ring. I'd never get it back." She got

it back.

She made good on her threats only

once, when someone spat on her. "I told him to stop,"

she explains. "But he kept spitting, and I was like, >You

know, if you spit any more, I'm gonna get you fucked

up<." He spat again, of course. "I saw the direction

from which the gob was coming, and I literally was tracing him as

the gob was flying at me. And of course, I found him. And the

rest of the fans in the area scattered and left the guy alone.

Then the security beat him senseless." Wow. "Well, I

mean, spitting is totally unacceptable, isn't it?" she

prompts with exaggerated, schoolmarmish hauteur. "Billy,

isn't it?" she asks the young man whose role, at this

moment, is to take apart her treadmill and put it back on the

bus.

She made good on her threats only

once, when someone spat on her. "I told him to stop,"

she explains. "But he kept spitting, and I was like, >You

know, if you spit any more, I'm gonna get you fucked

up<." He spat again, of course. "I saw the direction

from which the gob was coming, and I literally was tracing him as

the gob was flying at me. And of course, I found him. And the

rest of the fans in the area scattered and left the guy alone.

Then the security beat him senseless." Wow. "Well, I

mean, spitting is totally unacceptable, isn't it?" she

prompts with exaggerated, schoolmarmish hauteur. "Billy,

isn't it?" she asks the young man whose role, at this

moment, is to take apart her treadmill and put it back on the

bus.

"Yep," says

Billy. "Of course it is."

"This is Billy Bush. He engineered our record," she

says. "What else did he do? He programs practically

everything. He is Garbage. I'm just the face of Garbage; Billy is

the man behind it."

"The man behind the curtain," says Billy.

Someone else peeks into the room. "Oh, by God, we're trying

to work in here!" Shirley exclaims, feigning frustration.

"What is it now?" Just our backstage passes. Hers is

laminated, mine's a sticker.

"Let's see your one, " she demands. "Your one is

cooler than mine."

But yours is laminated!

"Yeah, but it doesn't say what it's for. I want it to say

Hole, garbage. That's cool. Ah, I don't know," she laments.

"People have no sense of occasion."

Yeah, it's like this happens every day or something like that, I

say sardonically. For some reason, this makes Shirley break out

laughing.

"Women are ridiculous," she says.

In fact, it is a fairly rare occasion for garbage to be sharing a

bill with Hole, and Shirley is genuinely jazzed about it.

"Courtney is a bundle of energy and excitement, intelligence

and rage," says Shirley. "It's exciting. I find her

adorable."

Billy quietly wrestles

with the treadmill, and the interview finally gets back on track.

Like many rock groups, garbage has bolstered its global profile

and record sales with extensive roadwork. The more than half-year

of touring behind 1998's Grammy-nominated Version 2.0 came on the

heels of the year-long recording and mixing sessions for that

album, which they started working on only six weeks after the

year-long tour behind their self-titled 1995 debut. Well, at

least they're used to the punishing grind of the road. It's even

been good for them.

"We've improved as

band live, because we've learned to actually listen, as in sense

how the audience is feeling." says Shirley. "That's the

excitement of playing live, when you get that kind of commune. So

you learn to watch your own energies on stage, as well as the

audience's." Thus, they decided to put they stripped-down ,

traditional-instruments-only version of Big Star's

"Thirteen" in the middle of the set, rather than using

it as an encore.

"It allows us to

muster our energies back," Shirley says. "I'm always

throwing parallels between the band and an army, but to me it's

like waging war. You have to pace yourself."

You also have to take

command of your arsenal. Through every second of Garbage's

hour-long Orpheum set, the players are in complete control. Steve

and Duke fire off stentorian, power-house blasts of guitar, while

Daniel Shulman's lively bass works complements both the

techno-industrial whizzing ad zizzing and Butch's rhythmic

thunder. It's a far cry from their early days, when the rigors of

reproducing their recordings' rich electronic textures in concert

made the musicians appear as mere components of digital behemoth.

Thanks to Bush, Garbage's very own Wizard of Oz, they are no

longer chained to the equipment.

"On the first tour,

we were really trapped by all the technology we were using,"

Shirley says. "It ran us. But on this tour, Billy was on top

of all the computers and the technology from day one. So when we

actually got to the point where we were playing live, it was

under control. It's allowed us a certain flexibility that people

don't believe is synonymous with machinery."

"I mean, it makes

life difficult for Billy," she continues sympathetically.

"He's had no sleep for the past three years, but our life

has been made simpler. And there's just more confidence. We're

willing to try different things, because he can fix it if

anything goes wrong."

"There's also a

bunch of new technology, which helps," Billy offers modestly

from the floor, still working on the treadmill.

"Billy goes to

these ghastly conventions and listens to all these computer nerds

go on about the newest gadget," Shirley says. "So we

were up on what was hip and happening, because Billy had spent

hours at that ghastly place."

PUSH IT

Techno-wizardry makes Garbage go, but the human core is

what makes this band tick. You might see that as a message in the

razzle-dazzle video for "Special," where the quartet

zip about in futuristic fighter planes, their arms and legs

entwined with the navigation and weaponry (which, at least in

Shirley's case, has a definite erotic angle. Or two.). Or you

might just see it as good silly fun, as Shirley methodically

destroys enemy pilots Duke, Butch and Steve, then blasts off

toward the horizon.

Whatever you see in it,

the video's slick, high-tech presentation immediately brings

dollar signs to mind. "I was like, 'Fuckin' hell, it looks

like we spent millions on this thing!'" Shirley exclaims. In

fact, she says, it cost a lot less than a lot of their other

videos. "Special" was designed and executed by Dawn

Shadforth, whose video for European dance band All-Seeing Eye

caught Garbage's attention last year while they were doing

promotion in France.

"She'd only done

three or four really small-budget videos, but you could see her

talent," says Shirley. "Her editing is really

musical." Shadforth's "Special" storyboard was the

most creative they'd seen. "It's very cutting-edge. It mixes

film with computer animation. It's like a Sony PlayStation game,

like Tomb Raiders come to life." They also loved the idea

because it isn't the first image the song brings to mind.

"It was so off-kilter from what we expected." She says.

"It's always good to surprise people."

And to keep them

guessing. So, does Shirley the space vixen make it to the rescue

beacon or not?

"Well, you don't

know," she says mysteriously. "I prefer to think that

she dies. It would be tedious with girl-kicks-guys'-ass. I like

the idea of girl dying kicking guys' asses. I like that she

overpowers them, but ultimately she fights it to the end. Rather

than that tedious 1980s idea of what feminism is about."

Which is?

"I loathe the idea

if female power," she explains. "I love the idea of

female equality." She takes a dim view of human nature in

general, and scoffs at the notion of female superiority. Still,

she believes that women are innately less violent than men,

partly because they have the biological potential to be

nurturers. "Everything that makes you up as a human being

plots your future," she theorizes. "Your biology, your

genes have a huge input into who you are and how you view the

world. Mind you, I'm a scientist's daughter, so I would say

that."

The middle daughter of a

geneticists and an amateur singer, Shirley Ann Manson wasn't

specifically encouraged to become the musician, but as a kid in

Scotland she took piano, clarinet and violin lessons, and sang in

a choir. Yet she didn't become involved with bands because she

pursued music, per se. It was more that the bands pursued her.

"I was a party girl," she says. "I was a big

showoff. I used to go clubbing a lot, so I was always at the

parties." The lead singer of her first group, Goodbye Mr.

MacKenzie, asked her to join because, she says, "he was soft

on me, basically."

The group released five

albums, charting in the UK at No.37 with a song called "The

Rattler" in March 1989. Shirley was one of the two keyboard

players then, though she occasionally played guitar and sang

backup. When the vocalist "couldn't continue singing, for

various reasons," she says, Shirley took the role. But the

band had already begun to disintegrate. She veered off with two

other members and formed Angelfish, which, she says, "was

really just a desperate attempt to keep making music."

Shirley had already

attracted the attention of Radioactive Records head Gary

Kurfirst, veteran manager of such seminal acts as the Talking

Heads. "He'd always said, 'If Goodbye Mr. MacKenzie goes

down the toilet, I want you to come to me. Because I think you're

amazing, and I think we could do something amazing ,

together'" she says. Angelfish sent him a hastily-made demo,

and before they knew it, they were recording an album with

producers Tina Weymouth and Chris Frantz.

"We found ourselves

in the States," she says, on tour with labelmates Live.

"I was totally unsure of myself [on stage], I was

uncomfortable, the band was uncomfortable. It was a nightmare

from start to finish."

In the end, her ticket

out of the bad dream came courtesy of the band's own video for

"Suffocate Me." Up in Madison, Wisconsin, Butch, Duke

and Steve needed a singer for their new project. With true

rock-legend serendipity, they tuned to "120 Minutes"

and saw Shirley the only time that MTV showed the video. Phone

calls were made, meetings held, and the rest, as they say, is

history.

WHEN I GROW UP

The Orpheum shudders under the dissonant electronic fury

of "Hammering In My Head." The air pulses and snaps

with an almost feral energy. Shirley is on her knees in the

black-and-blue light, growling. "I knew you were mine for

the taking when I walked in the room," she stage-whispers

into the microphone. It's just one riveting moment in a

performance that channels desperate devotion and nagging despair

with the offhanded ferocity of a natural dynamo. It is hard to

imagine she ever felt uneasy on stage.

Life offstage is more comfortable

for her, too. In fact, a girl could almost get used to it.

Shirley and I finish talking and join the others in the communal

area next to the dressing room. In a few minutes, a radio station

interview will begin. Duke mixes us each a giant plastic cup of

strong, citrus-spiked vodka and cranberry juice, "the

Garbage drink of the moment," he notes. A large gift-wrapped

box arrives for the band. "Presents?" Shirley thrills

from the dressing room. "I'll be receiving the gifts!"

She emerges and tears into the box, pulling out bags of candy, a

WBCN watch cap, a cheap toy car, and a big tube of alphahydroxy

hand lotion.

Life offstage is more comfortable

for her, too. In fact, a girl could almost get used to it.

Shirley and I finish talking and join the others in the communal

area next to the dressing room. In a few minutes, a radio station

interview will begin. Duke mixes us each a giant plastic cup of

strong, citrus-spiked vodka and cranberry juice, "the

Garbage drink of the moment," he notes. A large gift-wrapped

box arrives for the band. "Presents?" Shirley thrills

from the dressing room. "I'll be receiving the gifts!"

She emerges and tears into the box, pulling out bags of candy, a

WBCN watch cap, a cheap toy car, and a big tube of alphahydroxy

hand lotion.

She and Duke wander off,

leaving me with Butch and Steve. No longer filled with Shirley's

fast-paced chatter, the room falls momentarily silent.

"Are those Doc

Martens?" Butch asks, pointing at my battered, 10-year-old

Hawkins. He admires them, says he needs a pair of sturdy,

flat-bottomed shoes in which to play drums. He calls his black

low-top Simple sneakers "ugly." He has even colored the

pinkish rubber sides with a Sharpie to make them a little more

acceptable. "I had a pair of shoes that were perfect, but

Shirley thought they were so hideous, and she hounded me about

them so mercilessly, that I finally god rid of them," he

says.

I ponder just how much

hounding one could take from Shirley before caving in. No doubt

the members of Garbage have their disagreements, over wardrobe

and more serious matters. Yet they treat each other with real

kindness and affection. Their camaraderie is born of years spent

together in close quarters, both in studios and on tour, but it's

also a human necessity. Along with a handful of supporting

characters like Daniel Shulman and Billy Bush, these four people

are the only constants in their ever-changing universe of

highways, hotels, concert halls, fans and journalists.

Indeed, the pre-show

partying takes on an almost therapeutic glow. Or maybe it's the

vodka-cranberry a la Duke. As the room fills up with

well-wishers, business and pleasure cozily collide. Duke and

Butch profess their love for the Nuggets box set, saying it

inspired Garbage to record an "acoustic" version of the

Seeds' "I Can't Seem To Make You Mine," slated as a

future B-side. I put down my cup after finishing my second drink,

and Duke says, "I've had two of those, too." Mmm, I

feel pretty good right now, how 'bout you? He just grins.

Garbage surround their

radio-station interrogator, who engages them in a funny,

fast-paced chat. All goes smoothly until he questions Shirley

about a comment he says he read, in which she allegedly

proclaimed it easy to get men to want her. What advice do you

have, he asks, for any woman who wants to do this? It's a dumb,

loaded question, and Shirley confronts it head-on. "Just

pull your knickers down," she blurts, then breaks up

laughing and shouts, "Interview's over!" Dashing into

the dressing room, she gasps, "I can't believe I said

that!"

But she's famous for

being blunt, not just about sex but about most things. That's

just her nature. "I'm not the kind of person who walks into

a room and sees a steaming pile of shite and doesn't mention

it," she says. "I like to bring subject out into the

open."

Sure, Garbage's songs

are full of sexual imagery, and Shirley's been known to discuss

penis girth and other matters of the flesh in interviews. But

some male journalists have pegged her frankness as

flirtatiousness. "Well, men hear the word 'sex' or 'sexual'

-or 'sensual,' an even bigger crime-and it's like, 'Oooh, she's

talking about cocks ant tits,'" Shirley scoffs. At the same

time, she says, "a lot of women imply a sexual meaning to a

situation, in order to make somebody feel they might have a

chance with her." Men do it, too, he notes, but women are

better at it. "I am not at all flirtatious. I don't lead

people to believe they are going to have sex with me."

#1 CRUSH

When she wants to escape. Shirley reads. She's a

voracious reader. "it's the way to go when you need to shut

off," she says. She likes contemporary fiction, and is

well-versed enough to have penned an intelligent book review in

last April's Harper's Bazaar. Of course, she doesn't see it that

way.

"It was incredibly

traumatic for me," she moans. "I felt like a pompous

arse." Noooo. "Oh, are you kidding me? I felt

completely out of my depth. The only reason I did it, and I said

that in the article, was because I knew my father would get a

kick out of it. He has the article in his study, of course, and

he's very proud of it."

She rummages in a

shopping bag near my feet. "I'm actually reading this just

now," she says, producing a paperback novel by Scottish

writer Andrew Greig. "There's a great line in here that I

have to read to you, because it's my favorite line," she

enthuses. "It's just incredible. I love that, when you start

a book and you find a line that you're in love with."

"She searches for the passage. "I've been reading a lot

of Scottish fiction, because my husband brought it over."

(They rarely see each other, but got to spend Thanksgiving

together.) "I've read The Sopranos by Alan Warner; and

Purple America by Rick Moody, which is probably the last book

that I really, really loved." She keeps looking through the

book. "Sorry to do this when you've only got a few

minutes," she says. The suspense is killing me, though. I

have to know what she's looking for, as much as she has to find

it.

How did she like Bridget

Jones's Diary?

"It is funny,"

she concedes. "But it began to get on my nerves." She

is laughing at herself now. "Why can't I find this? It's

somewhere near here. I hope you like it, after all this."

More page flipping, scanning. "It's on this page, I know it

is. I've gone mad. I can't believe I'm doing this to you."

There's another knock at the door: Will Shirley be joining the

band for the soundcheck? She'll pass. "Oh, here it is!"

she exclaims. At last.

"Basically, he's

talking about pain. Or unpleasant things," she explains. The

epic instrumental roar of "Push It" wafts through the

wall. "And he says, 'These images will not leave me be, and

the reservoir is filled up to my throat, even to my mouth, so I

must stand a little taller before I dare speak with

friends.'" She lowers the book. "I mean, that's fucking

amazing."

Her intellectual habits

get a lot less attention than her cyber-vamp appearance, but

Shirley doesn't mind. Any attention she gets is good for the

band. But glossy images of herself seem as maddening as a plague

from the devil himself. "Why do I always have to look like a

geek on magazine covers?" she laments. "Why can't I

look hot?" Finally, she comes across a cover she can admire:

a solemn Shirley, gazing straight at the camera. "I look

like an alien in this one," she blisses.

THE TRICK IS TO

KEEP BREATHING

If the role of cover model is an uneasy one, the mantle

of musician and songwriter is even harder for her to accept.

Never mind that she co-produced Version 2.0 with the boys and

played guitar on it, not to mention writing almost every, word of

the lyrics. "I feel that I'm a charlatan to a certain

degree," she says, noting that it's partly because she

started so late in life. "A lot of my friends who are

creative say the same thing. It's like you constantly live in

fear of being 'found out' that you actually aren't good

enough."

She will admit that

she's getting better. "At the beginning of recording Version

2.0, I knew that, to a certain degree, I had to be the main

lyricist," she says. "I had to step up to the plate,

and that frightened me." For the first album, the entire

group scrutinized and edited her lyrics. With Version 2.0. she

simply wrote the lyrics and handed them over.

It still didn't work

quite like she had thought it would. Before they started work on

the second album, she had accumulated two huge notebooks full of

ideas. "I never used one of them," she says, "I

just went with the flow. We all got drunk and jammed, and all the

lyrics basically came from that." Maybe next time, she says,

she'll be confident enough to actually prepare lyrics in advance.

Of all the daunting aspects of

what has happened to her because of Garbage, fame itself is

perhaps the least distressing.

Of all the daunting aspects of

what has happened to her because of Garbage, fame itself is

perhaps the least distressing.

"We've enjoyed

extraordinary luck, as all successful people have, she says.

"I can accept that I've been lucky. I love the fact that

I've been lucky! It's the idea that. I might actually have a

modicum of talent that is still very alien to me."

The rewards of fame

aren't the privileges or the constant attention, which are

absolutely depressing and ultimately very empty and

meaningless," she says. "You feel that you have been

sucked by the vampire that is the world." But the symbiosis

with listeners makes it all worthwhile. "We're ordinary

people," she says, not superstars like Madonna was in the

'80s.

"People feel that

we're just like them, and they like that." Both the players

and their audience find self-affirmation in the music.

"Other people get off on our music because they recognize

themselves in it," she says, "and we get off on it

because they're recognizing us in it, or we feel we're being

recognized." Humans crave this connection, she says, but

"we've lost the ability to communicate. We don't really

express ourselves."

Warming to this thought,

she begins to talk faster, "So when someone else does it for

you, it's like in the olden days, when they used to cut you to

release disease." She mimes a slash across her forearm.

"You feel released. When you read a line or hear a song,

it's getting something out of you that you can't articulate

yourself. And you go back to that song, and you have your

feelings boxed for you and compartmentalized, and you can look at

it. And it makes you feel better. Rather than feeling that you

have this tumor eating away inside that's totally ambiguous and

intangible .... "

She stops herself and

shouts, "Waaaaah! Waa-waaaaaah! Come hear me talk a whole

lot of shite!" I want to protest that she's right, that

Garbage does make you feel better, that there is little else as

thrilling as their melt-in-your-mind grooves and larger-than-life

soul. But I'm laughing too hard. When the cackling stops, I ask

what it would take for her to not feel a fake. A certain amount

of maturity, maybe?

"Yeah," she

exhales. "I am still soooo unformed as a human being. Eight

months ago, I thought I'd got it all sussed out. As you do in

your life, you think, 'Okay, I see the world for what it is.' Six

months later, you realize you knew nothing. That's the wonderful,

great, amazing momentum in life. Your body deteriorates, your

face deteriorates, you lose your hair. But you gain a certain

peace and a grace that was not present when you were young. And

that's exciting!" She's getting charged up again. "I am

more and more energized, the older I get. I'm savage about life,

because I feel more alive now than I did when I was a teenager,

when I felt stuck in mud. I think a lot of teenagers feel like

that. That's the payback for having gorgeous skin."

AFTERGLOW

Garbage's backstage rooms, which were teeming with

people less than two hours ago, are quiet. Through the open panel

in the hall, Shirley and Billy watch Hole perform, huddling in

the dark so the audience won't see them peering out. They make

room for one more in the cramped space, and we look on in

comfortable silence as Courtney Love alternately praises and

berates the fans. On stage, Eric Erlandson bends his blond head

over his guitar, scarcely speaking or even looking up.

"Melissa is so skinny!' says Shirley. She compliments their

new drummer.

Time to get on the bus.

Garbage have to leave in about an hour for Hartford, Connecticut,

a few hours away. Then it's on to another show, and another. and

finally to Detroit after which, when they'll get about three

weeks off. Shirley expects to go home, see her husband. But

that's as much as she's willing to plan. "I have literally

refused to do anything," she says, "because I'm at the

end of my tether. I think I'll spend a lot of time in bed."

Home is still Scotland.

and will be until someday when she can afford to have a second

house, maybe in France or the US. Right now, she finds it's

healthy to go back, where her parents are, where people knew her

before she became famous. "It's good to go home and have

people say, "Hey, how you doing? How's your mum?" she

says. "I can switch off, wear no makeup, go hiking in the

hills, and forget all about the rest of the world." Home

also keeps her humble. "In Scotland, you don't get away with

any kind of attitude." she says. "If you're not normal,

you're gonna get called on it, to your face, in front of other

people." She laughs. "It can be a humiliating

experience."

Because the alcohol on

the bus is semi-cold beer, Butch proposes that everyone hit the

hotel bar for a round or two. "We've got half an hour,"

he says. Shirley gets carded, but she amiably fetches her

passport for the beleaguered waitress. I pick it up and examine

the cover: burgundy instead of navy, like American passports. She

teases me, "I know you want to look inside." So I do.

and, naturally, she derides the photograph. Then the call comes:

It's time to leave. There's a warm round of goodbyes, and then

the couches and chairs are empty. Garbage is back on the road.

As the Version 2.0 tour

keeps on rolling around the world, Garbage haven't even begun to

think about recording new material. First, Shirley says, they'll

work on a collection of international B-sides for US release

since "everybody's yelling for our B sides over here."

There are rare tracks and remixes to consider compiling as well.

And the boys will probably take up some producing projects.

"We just need some time before we start our third

record," Shirley says. "We have not stopped for

years."

Hell, at the rate

Garbage has been going, most people would've cracked up a long

time ago.

"I'm...yeah,"

she laughs softly. "I think I'm a monster."

With her high-riding crimson

ponytail and ultra-mod black eye makeup, Shirley Manson looks

like she just dropped in from some exotic planet. But when she

speaks, the siren of Garbage is unmistakably, delightfully human.

"I'm starving," she announces in a melodious Scottish

lilt. Her face is flushed from the chill wind of this deceptively

sunny Boston day. Settling at a nearby table in the hotel

restaurant, she talks about the photo shoot she's just finished.

"I have to get something to eat," she tells her

publicist. "But then I want to talk to you about

something."

With her high-riding crimson

ponytail and ultra-mod black eye makeup, Shirley Manson looks

like she just dropped in from some exotic planet. But when she

speaks, the siren of Garbage is unmistakably, delightfully human.

"I'm starving," she announces in a melodious Scottish

lilt. Her face is flushed from the chill wind of this deceptively

sunny Boston day. Settling at a nearby table in the hotel

restaurant, she talks about the photo shoot she's just finished.

"I have to get something to eat," she tells her

publicist. "But then I want to talk to you about

something." She made good on her threats only

once, when someone spat on her. "I told him to stop,"

she explains. "But he kept spitting, and I was like, >You

know, if you spit any more, I'm gonna get you fucked

up<." He spat again, of course. "I saw the direction

from which the gob was coming, and I literally was tracing him as

the gob was flying at me. And of course, I found him. And the

rest of the fans in the area scattered and left the guy alone.

Then the security beat him senseless." Wow. "Well, I

mean, spitting is totally unacceptable, isn't it?" she

prompts with exaggerated, schoolmarmish hauteur. "Billy,

isn't it?" she asks the young man whose role, at this

moment, is to take apart her treadmill and put it back on the

bus.

She made good on her threats only

once, when someone spat on her. "I told him to stop,"

she explains. "But he kept spitting, and I was like, >You

know, if you spit any more, I'm gonna get you fucked

up<." He spat again, of course. "I saw the direction

from which the gob was coming, and I literally was tracing him as

the gob was flying at me. And of course, I found him. And the

rest of the fans in the area scattered and left the guy alone.

Then the security beat him senseless." Wow. "Well, I

mean, spitting is totally unacceptable, isn't it?" she

prompts with exaggerated, schoolmarmish hauteur. "Billy,

isn't it?" she asks the young man whose role, at this

moment, is to take apart her treadmill and put it back on the

bus. Life offstage is more comfortable

for her, too. In fact, a girl could almost get used to it.

Shirley and I finish talking and join the others in the communal

area next to the dressing room. In a few minutes, a radio station

interview will begin. Duke mixes us each a giant plastic cup of

strong, citrus-spiked vodka and cranberry juice, "the

Garbage drink of the moment," he notes. A large gift-wrapped

box arrives for the band. "Presents?" Shirley thrills

from the dressing room. "I'll be receiving the gifts!"

She emerges and tears into the box, pulling out bags of candy, a

WBCN watch cap, a cheap toy car, and a big tube of alphahydroxy

hand lotion.

Life offstage is more comfortable

for her, too. In fact, a girl could almost get used to it.

Shirley and I finish talking and join the others in the communal

area next to the dressing room. In a few minutes, a radio station

interview will begin. Duke mixes us each a giant plastic cup of

strong, citrus-spiked vodka and cranberry juice, "the

Garbage drink of the moment," he notes. A large gift-wrapped

box arrives for the band. "Presents?" Shirley thrills

from the dressing room. "I'll be receiving the gifts!"

She emerges and tears into the box, pulling out bags of candy, a

WBCN watch cap, a cheap toy car, and a big tube of alphahydroxy

hand lotion. Of all the daunting aspects of

what has happened to her because of Garbage, fame itself is

perhaps the least distressing.

Of all the daunting aspects of

what has happened to her because of Garbage, fame itself is

perhaps the least distressing.