|

||

|

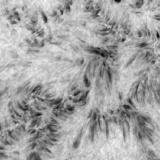

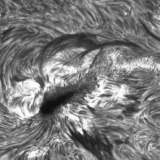

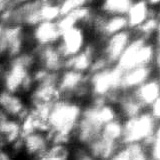

High-resolution view of the photosphere, showing bright

granules of rising gas and darker lanes of descending gas.

|

||

| SOLAR ACTIVITY | ||

| The Sun's surface is not a real surface, but rather is the depth into which we can see through the hot atmosphere. The layer we see is the photosphere, and it is a highly dynamic, seething surface populated by the most violent events of the Solar System. The main features of the photosphere are sunspots, flares, and prominences. | ||

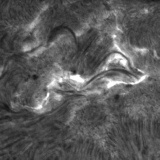

The photosphere, seen here in H-alpha light, is where the Sun's upwelling internal energy escapes into space. |

The chromosphere overlies the photosphere - bright areas are active regions. |

|

| Sunspots | ||

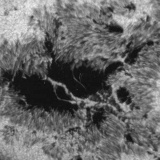

| Sunspots reside in the photosphere, and are large dark regions of strong local magnetism. The magnetic field of a sunspot prevents the escape of energy from below, and consequently sunspots have lower temperatures than the rest of the photosphere. However, sunspots only appear dark when viewed against the hotter, brighter surroundings. If you took a sunspot off the Sun and placed it in the night sky, it would shine very brightly. | ||

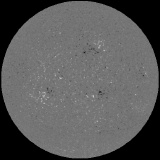

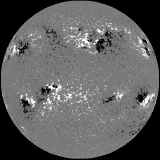

| Sunspots usually occur in pairs and are connected by magnetic field lines. One method of observing sunspots is to use magnetograms - images taken using slightly different parts of the spectrum corresponding to different magnetic polarity (north / south). This method reveals that a sunspot has the opposite polarity to the other member of the pair. The number of sunspots on the Sun's surface varies over an 11 year period - the solar cycle. However, the magnetic polarity of the Sun also varies on a 11 year cycle, with north switching to south and vice versa. This means that the solar cycle is really 22 years in length, with sunspot numbers reaching two maxima and two minima. | ||

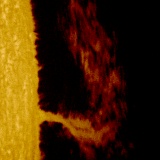

A sunspot viewed in the light of H-alpha. |

A very active sunspot, as seen here, produces massive flares. |

|

| The Sun is not completely free of sunspots during the solar cycle minimum, but numbers are greatly reduced. What few sunspots do occur are mainly found at higher solar latitudes. As the cycle progresses, sunspots are to be found nearer the Sun's equator. | ||

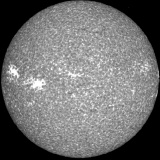

Solar magnetogram obtained during sunspot minimum. |

The Sun at sunspot maximum appears to be far more active. |

|

| Flares | ||

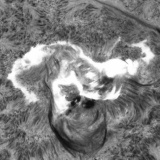

| Solar flares represent the most violent activity in the photosphere. Over a period of a few minutes, local temperatures climb to 5 million degrees, and huge numbers of particles and associated radiation are hurled into space. A flare usually lasts for less than half an hour. About a day later, there are impressive auroral displays above the Earth's polar regions as the particles interact with Earth's magnetic field. | ||

A bright flare erupting from a sunspot active region. |

A long and bright flare over 20,000 kilometres across. |

|

| Prominences | ||

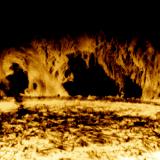

| The magnetic field lines that connect the members of a sunspot pair are capable of trapping large amounts of gas and keeping the gas suspended for several days in a huge arch. Such structures, the size of which dwarf Earth, are called prominences. They cannot be seen by the naked eye from Earth except during a total eclipse of the Sun. | ||

The solar corona and prominences are visible during a total eclipse. |

A ground-based view of a prominence on the Sun's limb seen in H-alpha light. |

|

Prominences are huge arches of gas suspended above the photosphere by magnetic forces. |

||

| Granulation | ||

| The photosphere is a very convective layer, and is broken up into individual convective cells called granules. A typical granule is 1100 kilometres across, and is slightly brighter than the surrounding inter-granular lanes. The temperature difference between a granule and a lane is about 400 K. The granules are areas where material is flowing upwards - the dark inter-granular lanes consist of descending material. A granule has an average lifetime of 18 minutes. | ||

High-resolution view of the photosphere, showing bright granules of rising gas and darker lanes of descending gas. |

||

|

|

||