|

|||

|

Voyager

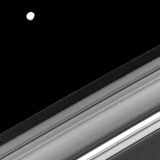

image of Saturn, Saturn's shadow across the rings, and Mimas.

|

|||

| MIMAS - MOON OF SATURN | |||

| Mimas was a giant. The son of Gaia, he personified the Earth. Mimas was one of the Titans slain by Heracles. Features on Mimas are named after characters and places from Thomas Malory's "Le Morte D'Arthur". Mimas was discovered in 1789 by Sir William Herschel, the discoverer of the planet Uranus. | |||

| Orbit | |||

| Mimas orbits at a distance of 185,520 kilometres from Saturn and has a very circular orbit which is inclined slightly (1.5o) to the plane of Saturn's equator. It takes Mimas over 22 hours to complete one orbit around Saturn. Mimas orbits within Saturn's E ring. | |||

Voyager view of Mimas orbiting beyond most of the rings. |

Voyager image of Saturn, Saturn's shadow across the rings, and Mimas. |

||

Mimas orbits beyond the brighter ring components. |

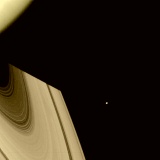

The orbits of Pandora, Janus, Epimetheus, and Mimas. |

Hubble Space Telescope image of Mimas, Tethys, Janus and Enceladus, clustered at the western side of the edge-on ring system. |

|

| Physical properties | |||

| Mimas is 392 kilometres in diameter, and is the smallest of Saturn's spherical moons. Those moons smaller than Mimas are all irregular in shape. It has a low density (1140 kg m-3 ), just a little over that of water. | |||

| Interior | |||

| The low density implies that Mimas consists mainly of water ice, with a small amount of rock. Little else is known of Mimas' structure, except that it has no heat source, and is cold and dead throughout. | |||

| Magnetic field | |||

| No magnetic field has been detected. | |||

| Atmosphere | |||

| No atmosphere has been detected. | |||

| Surface | |||

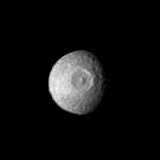

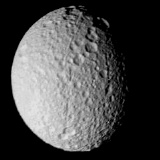

| In Voyager images it appears grey and heavily cratered. Mimas is famed for its particularly prominent crater Herschel. Herschel is one third the diameter of Mimas (130 kilometres across) and is estimated to be about 10 kilometres deep. Herschel Crater has a steep encircling rim about 5 kilometres high, and a large central peak which rises 6 kilometres above the floor of the crater. | |||

| Herschel and Mimas have one of the highest crater-to-planet size ratios in the Solar System. If the impacting object had been slightly bigger, it would have completely destroyed Mimas. | |||

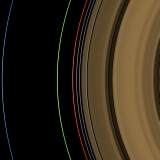

Voyager image showing the 130 kilometres wide Herschel crater. |

The object that formed Herschel crater came close to destroying the moon. |

||

| The central peak was formed by the rebound of the surface. During such an impact the surface momentarily behaves like a very soft, wobbly material; at the same time, shock-waves converge at the centre of the crater throwing up a peak. Mimas' low gravity and large proportion of ice to rock contribute to the large size of the peak (30 kilometres) which is more aptly described as a very big mountain. | |||

| Mimas' other craters are much smaller. The next largest, Bors Crater, is about 50 kilometres. There are however many hundreds of smaller craters. Those which we can see in Voyager images are mostly in the 10 to 20 kilometres size range and are quite simple, usually comprising a simple bowl shape. The high density of craters suggests that Mimas' surface is quite old, dating from the moon's formation. | |||

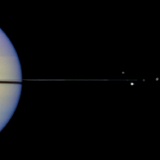

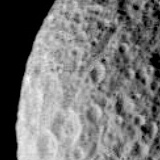

Mimas has a cratered surface, and this Voyager view also reveals canyons. |

|||

| Some researchers think that the lack of very large craters (except for Herschel) shows that Mimas has been broken apart and re-formed, while others suggest that they have been erased somehow. It is more likely though that the large older craters have simply been obliterated by smaller more recent impacts. Although badly disrupted, traces of very large old craters can still be seen. | |||

| Mimas has about five or six major valleys. They are about 10 kilometres wide and 90 kilometres long and are estimated to be about 1 to 2 kilometres deep. Those which we know of are in the southern hemisphere, because the coverage of the south is more complete. The valleys, or chasmata, are oriented northwest to southeast and may have been formed by tidal stresses or by a reduction in Mimas' rate of spin. | |||

Ossa Chasma, running from the craters Launcelot and Gwynevere. |

|||