|

|||

|

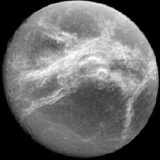

Hubble

Space telescope image of Dione orbiting Saturn

|

|||

| DIONE - MOON OF SATURN | |||

| The goddess Dione was regarded by some as the mother of Aphrodite. However, her name is actually the feminine form in Greek of Zeus (Dios). Dione is among the many discoveries of Italian born astronomer Gian Cassini, which he found in 1684. He had previously discovered Iapetus, Rhea, and Tethys. He also found a dark gap between Saturn's A and B ring, known today as the Cassini division. | |||

| Orbit | |||

| Dione orbits Saturn at a distance of 377,400 kilometres in an orbit that is nearly circular (eccentricity 0.0022). Dione orbits with a low inclination to Saturn's equatorial plane (0.02o), and takes 2.737 days to complete one orbit. Dione has a small co-orbital satellite, moving about Saturn on the same orbit. Originally designated 1980 S6 (Dione B), it was later named Helene. It orbits 60o ahead of Dione, in Dione's leading Lagrange point. Dione's orbit is also in resonance with Enceladus. Every time Dione orbits Saturn, Enceladus make two orbits. However, as Dione is more distant from Saturn, and is larger than Enceladus, tidal heating is unlikely to be significant. | |||

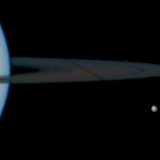

Voyager view of Dione and Tethys, with Tethys casting a shadow onto Saturn. |

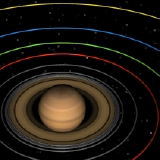

The orbits of Enceladus, Tethys, Telesto, Calypso, Dione, Helene, and Rhea. |

Hubble Space telescope image of Dione orbiting Saturn. |

|

| Physical properties | |||

| Dione has a diameter of 1120 kilometres, and is the third largest of Saturn's moons. (Rhea and Titan are larger). | |||

| Interior | |||

| Though Dione has a very low density (1403 kg m-3 ), it is still one of the densest of Saturn's moons. It is thought to comprise a small rocky core of between 60% and 70% water ice. Dione shows signs of internal activity. In appearance it is quite like Uranus' moon Ariel. Dione may well have undergone a similar evolution with expansion, caused by cooling later in its history, opening up wide canyons. One possible outline of Dione's geological past involves the early expansion of the moon caused by the heat from accretion to form fractures and grooves. This occurred against a background of heavy cratering. | |||

| Heat from the decay of radioactive elements in Dione's interior may have melted the crust and resurfaced it in places. As the crust cooled it initially expanded, forming troughs which later filled with volcanic materials (ice). Further cooling eventually led to contraction of the surface, forming topographic ridges. The details of Dione's evolution are far from clear and the extent of volcanic activity is still uncertain. As Dione is fairly small, the heat from accretion and decay of radioactive materials was dissipated quite rapidly. Dione therefore has probably been inactive for several thousand million years. | |||

| Magnetic field | |||

| No magnetic field has been detected. | |||

| Atmosphere | |||

| No atmosphere has been detected. | |||

| Surface | |||

| Although Dione was imaged by both of the Voyager spacecraft there is a large gap in the coverage between longitudes 80o and 200o. The surface was not imaged at close range and the best images contain only features larger than 2 kilometres. | |||

| Dione has a moderately bright surface (albedo 0.5), in common with Rhea, because it is largely ice. There is a difference though between the albedo of the leading hemisphere (facing the direction of travel) and the trailing hemisphere. The leading hemisphere is darker (albedo 0.3). It is thought that this is because the leading side is hit more frequently by small meteorites which disrupt and dirty the surface. From this it is inferred that Dione has been locked in its current orbit for a few thousand million years. (Iapetus, conversely, has a brighter leading hemisphere). | |||

| Dione features three types of terrain. Though there are no sharp divisions between the different surface types, they are easy to distinguish. There are heavily cratered regions, moderately cratered regions, and smooth plains which have a low crater density. In places, overlying these surfaces, are bright wispy materials. | |||

| The heavily cratered surfaces have a very broad range of crater sizes, from a few kilometres to over 200 kilometres, like Aeneas Crater. The number of large craters, but lack of giant impacts, suggests that these surfaces date from after the "great bombardment" period but from a time when the meteorite population was still quite high. | |||

Voyager 1 image of Dione's largest crater, Aeneas (bottom). |

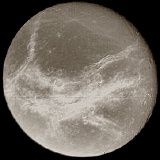

Dione's leading hemisphere is heavily cratered. The largest crater is Dido. |

||

| The moderately cratered regions still have a very large number of craters but these are in a smaller size range. The smooth plains have a far lower density of craters. Those craters that have formed in the smooth plains are generally less than 30 kilometres across. | |||

| Most of the heavily cratered terrain is found on the trailing hemisphere and the less cratered plains on the leading side. Collisions were expected to have occurred more frequently on the leading edge. So why should the opposite be true? What might have happened is that Dione was hit by a large meteorite. As Dione is fairly small, any of the larger impacts could have caused Dione to wobble or spin around. | |||

| The bright streaky bands across Dione's surface are the trailing hemisphere's most striking characteristic. Close examination of Voyager images shows that they are in fact troughs. The best example is the 600 kilometre long Palatine Chasma. It is irregular and has rugged scarp faces. | |||

Bright, wispy streaks on Dione's trailing hemisphere as seen by Voyager 1. |

|||

| In some places the streaks are wispy and mantle the surface without obscuring the detail of the features they cover. However, most of the deeper troughs appear to be filled by a smooth icy layer, perhaps erupting through cracks opened up by expansion of Dione's surface. | |||

| Some researchers argue that Dione has been more volcanically active than previously thought. There are though, many features which are possible to interpret as having a volcanic origin, but are too ambiguous to identify with certainty. Regions which have fewer craters or are flatter and smoother than their surroundings are sometimes described as lava fields formed by recently erupting ice. Chains of craters and pits can be described as vents for erupting material. These could just as easily be formed by meteorite or cometary impacts. | |||

The bright streaks dominate this Voyager view acquired at a distance of 620,000 kilometres |

|||

| There are also scarps and ridges. These are mostly found in the heavily cratered terrain. The ridges are most prominent. They are crooked and vary in width but are generally about 5 to 10 kilometres wide and about a kilometre high. The longest extends for about 300 kilometres. The ridges are thought to have formed in an episode of compression. Though not the youngest features on the surface (they have lots of small craters), they probably represent the later stages of Dione's geological evolution. | |||

|

|

|||