|

|||

|

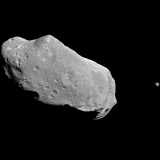

Galileo view of Ida and Dactyl from 16,000 kilometres.

|

|||

| ASTEROID IDA-DACTYL | |||

| Ida is named for the nymph who raised the infant Zeus (the Greek equivalent of the Roman god Jupiter). Ida is also the name of a mountain on the Greek island of Crete, the site of the shrine and cave where Zeus was brought up. Accordingly, the craters on 243 Ida's surface are named after famous caves around the world, like Mammoth and Lascaux. Ida was discovered by Johann Palisa in 1884.Ida was the second asteroid to have been observed at close range by spacecraft. Ida was encountered on August 28th 1993 by the Galileo spacecraft which passed less than 2,400 kilometres from it. | |||

| Orbit | |||

| It orbits at an average distance of 270 million kilometres from the Sun and has a rotation period of 4 hours 38 minutes. Ida is part of a group, or asteroid family, known as the Koronis. Its relatively rapid rotation meant that Galileo could obtain high resolution images of the whole surface. | |||

Ida's orbit. |

The rapid rotation of Ida is apparent in this 5 hour approach sequence. |

||

| Physical properties | |||

| Ida is a fairly sizeable asteroid, twice as big as Gaspra. Ida is quite elongated and measures 58 kilometres x 23 kilometres. It is slightly crescent-shaped and narrower in the middle than at the ends. This led to early speculation that Ida had formed from two separate bodies which somehow combined. Ida is classified as an S-type asteroid like 951 Gaspra. Galileo was able to provide a more accurate determination of Ida's mass, and therefore its density. The density of Ida, 2900 kg m-3, is lower than was expected, indicating that the asteroid is metal-poor. Similar to a stony iron meteorite it probably contains nickel, iron, magnesium, and silicate rocks. The low density indicates it may contain only a little metal, its parent body having not fully differentiated. Alternatively, it may just be poorly compacted and have large internal voids. Nevertheless, its density is still markedly higher than that expected from the more common C-type or chondritic asteroids. | |||

Ida comparison with Earth. |

|||

| Atmosphere | |||

| No atmosphere has been detected. | |||

| Magnetic field | |||

| Galileo recorded fluctuations in the solar magnetic field as it passed Ida. The variations in the field suggest that despite its relatively low density, Ida comprises at least some magnetic material. | |||

| Surface | |||

| In visible light Ida appears grey. Images were obtained in infrared wavelengths by Galileo's Near Infrared Mapping Spectrometer instrument and reveal subtle colour variations in Ida's surface. Enhanced colour pictures are made from combining images recorded at violet, red, and infrared wavelengths. In enhanced colour images light blue regions can be seen around craters. There are small bright blue craters with sharp edges. There are larger blue halos around some craters, but these are more diffuse. The ejecta appears blue because it reflects blue light and absorbs near infrared light. This was at first thought to indicate a difference in the abundance of iron minerals. | |||

Galileo image of Ida, from 10,870 kilometres. |

Increased colour enhancement reveals blue ejecta on the surface of Ida. |

Enhanced colour view of Ida from a distance of 10,500 kilometres. |

|

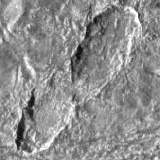

| The colour variation is affected by the surface's physical properties as well as its chemical composition. The surface is highly weathered by impacts which have churned up the surface creating a loose rocky soil. This shields the interior from radiation and small meteorite impacts until a large object arrives and excavates fresh rock from deeper within the asteroid. The surface of Ida is heavily cratered, and it is therefore probably safe to assume that it's quite old. There are many small craters which look pristine and are quite likely young, these are superimposed upon larger craters which have a degraded, more rounded appearance. | |||

The heavily cratered surface of Ida. |

Galileo was 3,600 kilometres from Ida when it acquired this high-resolution image showing Ida's cratered surface. |

||

| The great age of Ida does not fit with what has generally been presumed of its origin. It was thought that belonging to the Koronis family, it would have been formed when a single large object, 200 to 300 kilometres across, was broken apart in a relatively recent collision. Given what is known about the surface and composition of Ida, either the Koronis break-up theory is flawed, or Ida was formed somewhere else. The number and size of craters on Ida's surface indicate that it is at least 1000 million years old. | |||

| Ida's moon | |||

| Images taken by Galileo during the flyby of Ida revealed a small moon in attendance - Ida has its own moon. Though the existence of asteroid satellites had been tentatively indicated by Earth-based observations, Dactyl or (243) Ida I, is the first confirmed asteroidal satellite. Double craters, craters which share a rim and appear to have formed simultaneously, occur on rocky bodies throughout the Solar System and suggest that binary or double asteroids are very common. Though merely circumstantial, the fact that one of just four close passes of asteroids have revealed a satellite, makes it seem very likely that more will be found. The image here shows a double impact crater on the surface of Ganymede, possibly formed by a double asteroid. | |||

Oblong craters formed by double asteroid impact. |

|||

| Dactyl is named after the Dactyli, a group of mythical creatures that lived on Mount Ida and protected the infant Zeus. In some legends they are the children of the nymph Ida and Zeus. Dactyl orbits Ida at a distance of approximately 90 kilometres. It is very small, about 1.6 x 1.2 x 1.4 kilometres. For such a small body it is remarkably spherical. The Galileo spacecraft caught Dactyl in an image intended to form part of a high resolution mosaic of Ida. The best image of Dactyl has a resolution of about 40 metres. The image reveals a hummocky and cratered surface. The larger craters appear to have excavated bright material. The largest visible crater is about 300 metres across, has a sharp rim, and looks quite deep. | |||

The most detailed picture of Dactyl, obtained by Galileo at a distance of 3,900 kilometres. |

|||

| Dactyl's surface has similar spectral properties to Ida; it is therefore probably similar in composition, though there are slight differences at some wavelengths. Dactyl's mass and density were calculated from its orbital properties. Its density is between 2.2 and 2.9 kg m-3, a loose estimate because Dactyl's orbit is not known with any great accuracy. Its density is low, but like Ida, it probably contains a little metal and is a stony-iron body. One of the biggest unanswered questions is how did Dactyl end up in orbit about Ida ? | |||

| It is thought highly unlikely that Dactyl is a captured asteroid which formed elsewhere, unless it was moving extremely slowly in relation to Ida. Dactyl may be a piece of Ida which was broken off or ejected in a collision. The favoured scenario involves the original formation of the Koronis family. After the collision which formed the group, some of the fragments remained close together; some small fragments ending up in orbit around the larger and gravitationally more powerful bodies. | |||

|

|

|||