Pain Assessment: Pain assessment content is included in most textbooks with fundamentals of nursing and medical surgical content. The following book chapters follow the basic pain assessment outline presented in this topic. Wilkie, D.J. (2000). Pain perception and comfort. In R. Craven & C. Hirnle (Eds.), Fundamentals of nursing: Human health and function (3rd ed.) (pp. 1141-1172). Lippincott:� New York.1 Wilkie, D.J. (2000).� Nursing management: Pain.� In S.L. Lewis, M.M. Heitkemper, S.R. Dirksen (Eds.), Medical-surgical nursing: Assessment and management of clinical problems (5th ed) (pp.126-154). Mosby:� St. Louis.2 The content in this module is presented as a teaching manual and supports an interactive lecture with active engagement of the students using questioning and case examples. Teaching Manual for Pain Assessment Content Our society uses the word pain to denote sensory and emotional distress.� Hence, the word pain means different things to different individuals. Students need to adopt a professional language and a common understanding of what pain is and is not. Emphasizing the differences among pain, nociception, and suffering helps students unlearn the lay definitions and adopt professional definitions. These definitions set the stage for the notion that pain is variable from person to person. DefinitionsThe clinical definition of pain specifies that "Pain is whatever the experiencing person says it is, existing wherever the person says it does." 3 Similarly but more specific, the scientific definition of pain specifies that "Pain is an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage." 4 The scientific definition helps the nurse to target further assessment and management strategies more specifically than the clinical definition, but both definitions focus on the subjective nature of pain. Several other definitions are related but not equated with pain. Nociception is the activation of primary afferent nerves with peripheral terminals that respond differentially to noxious (i.e., tissue damaging) stimuli. Nociception may or may not be perceived as pain, depending upon a complex interaction within the nociceptive pathways.5 In contrast suffering, which often is equated with pain is "the state of severe distress associated with events that threaten the intactness of the person."6 According to these definitions, it is clear that pain, nociception, and suffering are related but not the same concept. Pain as a multidimentional phenomenon

Affective dimension: emotions, such as

fear, anxiety, depression, anger, hope, joy. This dimension includes emotional

responses to pain that are cultural in origin.

The goal of a nursing pain assessment is to sort out the pain assessment data in order to conclude if the pain experienced by a person with a life limiting illness is nociceptive, neuropathic or both types of pain. Determining the impact of the affective, cognitive and behavioral components of the pain also is a goal of a nursing pain assessment. The nursing pain assessment allows the nurse to apply pain relief strategies specific to the type of pain. Who Assesses? � Who is the Expert? Physicians and nurses are the experts about how to treat diseases and manage pain. But it is the patient with pain, who is the expert about how the pain feels. Emphasize to the students that patients do not recognize that it is they the patients who are the experts. Patients assume that because health care providers have provided care to so many patients with the same disease as the patient, patients often believe the providers must surely know how they feel. Health care professionals only know how a person's pain feels if the person tells or shows them. Students must help patients to own their expertise and be a partner with the providers in order for pain management to be most effective.� It is through the pain assessment process that the nurse helps patients own and share their expertise about the pain, its relief and its meaning. People with pain report that sometimes it is difficult to tell others about the pain because it is hard to describe with words. Students also need to understand that the pain assessment process helps patients to tell others about the pain. This module will help the student to systematically monitor a patient's pain and document or communicate it in a way that will help other health professionals understand how it feels. When health professionals know how it feels, it is easier for them to prescribe the best therapies to relieve the patient's pain. There are many resources to help patients talk with their health care provider about their pain. Family members may or may not understand sufficiently about the patient�s pain to be a proxy in the pain assessment process.� Many studies have shown that families are reliable when reporting the presence or absence of pain to health professions.� Family members are less reliable when it comes to reporting the intensity, location, quality or pattern of the patient�s pain.� Some family members underestimate, others overestimate and a few family members are precise when compared to patient self-report of pain. Family members assume a great deal of responsibility for assessing pain in people facing the end-of-life transition. Students need to see the difference between curing a disease or illness as a means of treating pain (primary treatment plan for most painful conditions) and palliating all pain. A good example is right upper quadrant pain, exacerbated by eating a fatty meal. Ask students: What is a likely cause of that pain?� (Gallbladder disease) What is the treatment(s) that will cure that pain?� (Surgery) What are likely palliative treatments for that pain?� (Pain medications)� Is the cause of the pain after the surgery the same as before surgery?� (No, it's likely to be post-operative incision pain) What is the cure for this new pain?� (Time, as wound healing occurs) What are likely palliative treatments for this new pain?� (Pain medications) This example also provides a good opportunity to discuss the notion of pain medication for abdominal pain after the medical history and physical exam have been completed.� Since medical decisions do not require ongoing pain, it is unethical to withhold palliative treatment for abdominal pain once the patient has been examined and while the curative treatment plan is formulated and implemented. The main idea here is that all patients should have their pain palliated. Palliative care is not just for dying people, but for all of us when we have pain. A common belief is that pain can be assessed but it cannot be measured. Assessment is the act of determining the importance, size, or value of something. In contrast, measurement is the act or process of applying a metric to gauge something. Health professionals, however, consider other subjective phenomena to be measurable. For example, vision is a subjective phenomenon, yet a metric can be applied to determine visual acuity (e.g., Snellen Eye Chart) and ability to see color.� Pain can be measured in a similar way by including valid and reliable metrics (tools or scales) of the pain experience as part of the pain assessment process. Use visual acuity, visual color perception, and auditory acuity as examples of subjective phenomenon for which measurement tools have been developed and tested in order to reverse (relieve) sensory alterations. (Learning activity 1) Guide students to accept that measurement of pain location, intensity, quality and pattern is similar when standardized tools are used. Many tools are available to measure the sensory components of pain (pattern, area, intensity, and nature). Fewer tools are available to measure the affective, behavioral, and cognitive pain components in clinical practice. Therefore the nurse can measure pain pattern, area, intensity, and nature with such tools as the McGill Pain Questionnaire.� Fewer tools are available to measure the affective, behavioral, and cognitive pain components, so the nurse must assess affective, behavioral, and cognitive pain components as the patient's history is obtained, at least until valid and reliable measures also become available for these components. Physiological dimension Sensory dimension

Location and distribution of the pain. Patients with cancer pain often have pain in multiple sites of the body, usually 2 to 4 sites, but up to 14 sites have been reported. Location of pain

Intensity or severity (varies tremendously from person to person and often is not a good indicator of pain etiology)

Quality or descriptors of the nature of the pain This information is very important to understanding if the pain nociceptive or neuropathic? Some verbal descriptors are indicative of neuropathic pain and others of nociceptive pain when used in conjunction with the pain location, intensity, and pattern data as well as data from the history and physical exam. A list of descriptors is provided with the research base to support the words as nociceptive or neuropathic words. Provides a clue to appropriate drug to relieve pain (e.g., adjuvant

drugs for neuropathic pain, anxiolytic drugs for anxiety): Gives a clue regarding the need for emotional support (emotional words) Gives a clue regarding the patient�s ability to cope (evaluative words suggest patient�s coping reserve) Temporality or the pattern of the pain, meaning how it changes with time

How to report this information to other health professionals

Documentation is essential (e.g., in the medical record or patient�s chart). Document pain assessment information in a location that is easy to access by all health care providers. Even the best pain assessment conducted by one nurse is of limited value unless the information gained is shared with other nurses and other health care professionals responsible for care of the patient with pain. Use the documentation tools provided by the agency for this purpose. If the agency doesn't have specific pain assessment tools, talk to the supervisor about developing some. Until documentation forms are available, use the progress notes and flow sheets to document findings from pain assessments. Usually there are blank sections on flow sheets that can be easily modified to document pain sites, intensity numbers, and quality and pattern words.

Importance of health professionals examining their

knowledge, beliefs, and attitudes about pain and pain management

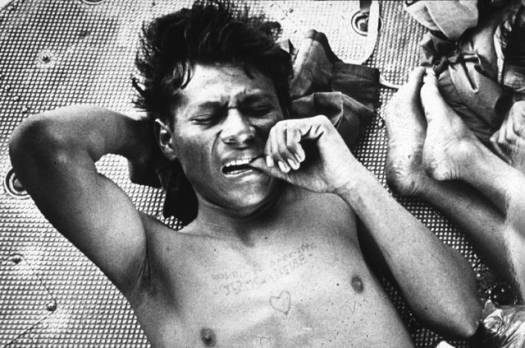

Affective Dimension Negative emotions: Patients with unrelieved pain often have concurrent emotional responses that can intensify the pain sensation, such as anger, fear and anxiety. These emotions stimulate the autonomic nervous system. Norepinephine release resulting from stimulation of the sympathetic nervous system enhances pain intensity in both nocicpetive and neuropathic types of pain.� As well depression is associated with alteration of amine (e.g., serotonin and norepinephrine) function in the CNS, which may reduce effectiveness of the descending pain inhibition system. All of these emotions are common in people with life-limiting illness. Control of these negative emotions is important to reducing pain. Positive emotions: Emotions such as joy, humor and laughter may decrease the amount of pain perceived by persons with pain. The mechanisms by which these emotions facilitate pain relief are not clearly known. Evaluation of the positive and negative emotions can help to determine the amount of suffering experienced by patients. This determination is important because suffering is treated differently than pain. For example, opioids are not very effective for suffering but can be the choice treatment for pain. Antidepressant and antianxiety drugs as well as active listening may be useful in treatment of both pain and suffering. Behavioral Dimension Medication adherence:� Despite the effectiveness of analgesic medications, many patients do not adhere to the prescription for a variety of reasons. Cost of the pain medication may be a barrier that leads the patient to reduce the dose in order to make the prescription last as long as possible. Drug side effects, if not well controlled often cause the patient to stop taking the pain medication. Many other reasons related to non-adherence are related to their beliefs, attitudes and expectations. Understanding these issues are important for nurses to effectively implement a pain relief plan. Pain control behaviors:� Patients with pain engage in a number of behaviors to control their pain (reduce pain, prevent pain onset, reduce pain duration, and tolerate the pain) (Table 1). For example, watching television or talking with friends, staff, or family members helps to distract patients from their pain and can be very effective in helping to control pain. Patients may endure pain when they are unaware it can be relieved. How patients comply with or adjust analgesic therapy plans is also an important aspect of patient pain behavior. Often people in severe pain are judged by clinicians to be in a pain-free state, mainly because clinicians do not appreciate the complexity of pain behavior. The videotape of Mr. C (Case section) shows many of the behaviors listed in Table 1. Click to view Table 1.� Validated Pain Control Behaviors from Videotaped Observation7 Facial expressions also are poor indicators of the amount of pain experienced in people who face the end-of-life transition. Figure 1 shows a photograph of a person at risk for death due to a serious war injury. The soldier engages in pain control behaviors as well as has the typical grimace associated with pain. People with lung cancer, never showed this grimace expression during a 10 minute videotape session in their homes in which they sat, stood, walked and reclined, behaviors that commonly stimulate pain in this population. Instead, as Tables 2 and 3 show, the people facing death from their cancer and experiencing pain most frequently made small wincing expressions (action units 6 or 7). The most frequent facial muscle that moved on their faces was the cheek raiser (orbicularis oculi, pars orbitalis muscles). That type of facial movement is very easy to miss, especially if one is observing to see the grimace expression shown in Figure 1. Figure 1.� The typical facial expression of pain is illustrated

by a wounded soldier. He bites his thumb, a type of pain control behavior,

as he is transported for treatment of an injury. This expression rarely

occurs on the face of persons with chronic cancer pain while engaging

in activities of daily living in their homes.(San Francisco Examiner

photo by Kim Komenich, reprinted with permission.)

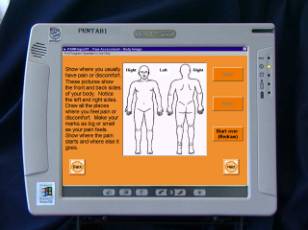

Click to view Table 3: Frequency, Mean, Standard Deviation, and Median for Pain Profile Action Unit Scores Observed in 42 Patients with Lung Cancer Pain.� Patients were Observed for 10 Minutes while They Ambulated, Sat, Stood and Reclined in Their Own Homes. Cognitive Dimension Beliefs: Meanings associated with and beliefs, attitudes, and expectations about the disease (e.g., cancer, Alzheimer�s, ALS) and about pain can influence patient response to pain therapy.� Just as belief in the effectiveness of an analgesic can lead to a placebo response, other beliefs can affect pain perception, although the mechanisms are unknown. Beliefs about pain, the illness, attitudes about pain medications and other therapies, and expectations about pain relief are important cognitive dimension elements. Helping patients to expect that pain relief is possible is an important nursing intervention for all people, but especially for people at the end of life. Goals for pain management: A patient's goals for and expectations about pain relief and treatment outcomes are crucial in understanding cognitive aspects of pain.� Goals of treatment, however, must be realistic and attainable given the patient, health care providers and environment. Determining the optimal goal (usually 0 pain for 90% to 95 % of people with advanced cancer) as well as the goal with which the patient will be satisfied (usually 1 to 4 on a 0 to 10 scale) helps to evaluate progress being made in pain relief. Research suggests that health professionals may expect patients to tolerate some pain, especially if the pain does not interfere with the patient�s function. This moderate level of pain, however, is inconsistent with the patients� goals. Family member�s goals may mirror the patient�s but may not if the family is concerned with the patient�s level of consciousness. This area of pain assessment is facilitated when the patient�s wishes are know and family members are comfortable with those wishes.� Past experiences with pain and pain relief:� A person�s past experiences with pain and pain relief provide insight into the person�s responses to different therapies and the person�s coping with pain. This information gives a clue to the person�s biologic makeup (genetics) and psychological tendencies.� Other cognitive factors: such as level of consciousness (sedation level), dementia, memory of past pain, source of motivation (internal versus external locus of control), and cognitive resources to cope with the pain can dramatically influence the pain experienced by the person with pain. For example, a person who is very active and like to take control may do best when� he/she is involved in planning care and in developing a very structured pain management routine. Pain assessments are needed initially when care is provided as well as in follow-up after therapy.� The type of information collected at each assessment should guide ongoing therapy decisions. Initial Assessment Follow-up Assessment Each new pain, particularly unexpected intense pain, needs to be evaluated promptly. In the person facing the end-of-life transition, treatment of the primary cause of a new pain site will depend on the patients� goals for care.� For example, a person facing death from lung cancer may choose not to treat chest pain believing that death from a heart attack is less distressing than death from lung cancer.� Another person in the same situation may want aggressive treatment of the heart attack. Careful pain assessment and evaluation of the pain within the context of the patient�s wishes for end-of-life care provides important information for treatment planning. Although there is no valid and reliable pain measurement tool that measures all aspects of the pain experience, the McGill Pain Questionnaire captures many elements. The McGill Pain Questionnaire is available in a computerized format that allows patients to document their pain using touch screen technology or a mouse if they prefer (Figure 2). Ask students to use the McGill Pain Questionnaire10 to measure the sensory components of pain.� Ask the students to use the directions for use of the McGill Pain Questionnaire. These directions describe how to use the tool to collect subjective pain data in a standardized way.�

If students use the tool before the pain assessment class, their experiences can be used throughout the class session to actively engage the students in an interactive learning environment.� To stimulate the class, ask the following questions. What kinds of things did you do to make this pain assessment work

well for you or the person you assessed? Use student's answers as case examples to explicate the sensory pain assessment content shown on the slides. Figure 2. Example of PAINReportIt, the first computerized McGill Pain Questionnaire. This screen shot shows the body outline on which a patient can draw the location of his/her pain on the Fujitsu pentab computer, a small etch-a-sketch appearing touch screen computer.

Another way to demonstrate a pain assessment is to play the audio clip of the pain specialist collecting sensory pain data from a young man. This example can be used as a case example to explicate the sensory pain assessment content in the lecture slides. There are a number of other tools that can be used to assess pain (Table 4) . The Pain-O-Meter has been tested in several studies. For children and teenagers, the Adolescent Pediatric Pain Tool provides information similar to the McGill Pain Questionnaire. Children complete this multidimensional tool in less than 5 minutes.11 Several other tools are available to measure pain intensity. The Wong-Baker faces scale has been used extensively to measure pain intensity in children. The OUCHER is another pain intensity tool that has been tested extensively in children. Also consider the following pain assessment scales: McGrath faces, Pediatric color VAS, and Italian color VAS.

|

||||||

©2001 D.J. Wilkie & TNEEL Investigators